Geominerals/Silicates: Difference between revisions

imported>Marshallsumter |

(No difference)

|

Latest revision as of 07:06, 17 May 2022

The geominerals of silicates is an effort to determine which silicates are on Earth and the geochemical reason why from a thermodynamics perspective.

Silicate perovskite is either Template:Chem (the magnesium end-member is called bridgmanite[1]) or Template:Chem (calcium silicate) when arranged in a perovskite structure. Silicate perovskites are not stable at Earth's surface, and mainly exist in the lower part of Earth's mantle, between about Template:Convert depth. They are thought to form the main mineral phases, together with ferropericlase.

The existence of silicate perovskite in the mantle was first suggested in 1962, and both Template:Chem and Template:Chem had been synthesized experimentally before 1975. By the late 1970s, it had been proposed that the seismic discontinuity at about 660 km in the mantle represented a change from spinel structure minerals with an olivine composition to silicate perovskite with ferropericlase.

Natural silicate perovskite was discovered in the heavily shocked Tenham meteorite.[2][3] In 2014, the Commission on New Minerals, Nomenclature and Classification (CNMNC) of the International Mineralogical Association (IMA) approved the name bridgmanite for perovskite-structured Template:Chem,[1] in honor of physicist Percy Williams Bridgman, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1946 for his high-pressure research.[4]

The perovskite structure (first identified in the mineral perovskite occurs in substances with the general formula Template:Chem, where A is a metal that forms large cations, typically magnesium, ferrous iron, or calcium. B is another metal that forms smaller cations, typically silicon, although minor amounts of ferric iron and aluminum can occur. X is typically oxygen. The structure may be cubic, but only if the relative sizes of the ions meet strict criteria. Typically, substances with the perovskite structure show lower symmetry, owing to the distortion of the crystal lattice and silicate perovskites are in the orthorhombic crystal system.[5]

Bridgmanite is a high-pressure polymorph of enstatite, but in the Earth predominantly forms, along with ferropericlase, from the decomposition of ringwoodite (a high-pressure form of olivine) at approximately 660 km depth, or a pressure of ~24 GPa.[5][6] The depth of this transition depends on the mantle temperature; it occurs slightly deeper in colder regions of the mantle and shallower in warmer regions.[7] The transition from ringwoodite to bridgmanite and ferropericlase marks the bottom of the mantle transition zone and the top of the lower mantle. Bridgmanite becomes unstable at a depth of approximately 2700 km, transforming isochemically to post-perovskite.[8]

Calcium silicate perovskite is stable at slightly shallower depths than bridgmanite, becoming stable at approximately 500 km, and remains stable throughout the lower mantle.[8]

Bridgmanite is the most abundant mineral in the mantle. The proportions of bridgmanite and calcium perovskite depends on the overall lithology and bulk composition. In pyrolitic and harzburgitic lithogies, bridgmanite constitutes around 80% of the mineral assemblage, and calcium perovskite < 10%. In an eclogitic lithology, bridgmanite and calcium perovskite comprise ~30% each.[8]

Calcium silicate perovskite has been identified at Earth's surface as inclusions in diamonds.[9] The diamonds are formed under high pressure deep in the mantle. With the great mechanical strength of the diamonds a large part of this pressure is retained inside the lattice, enabling inclusions such as the calcium silicate to be preserved in high-pressure form.

Experimental deformation of polycrystalline Template:Chem under the conditions of the uppermost part of the lower mantle suggests that silicate perovskite deforms by a dislocation creep mechanism. This may help explain the observed seismic anisotropy in the mantle.[10] Template:Clear

Cyclosilicates

Def. any group of silicates that have a ring of linked tetrahedra is called a cyclosilicate. Template:Clear

Abenakiite-(Ce)

Abenakiite-(Ce) has the chemical formula Template:Chem. Abenakiite-(Ce) (IMA1991-054; IMA Symbol Abk-Ce[11]) is a mineral of sodium, cerium, neodymium, lanthanum, praseodymium, thorium, samarium, oxygen, sulfur, carbon, phosphorus, and silicon. The silicate groups may be given as the cyclic Template:Chem grouping. Its Mohs scale rating is 4 to 5.[12]

Abenakiite-(Ce) was discovered in a sodalite syenite xenolith at Mont Saint-Hilaire, Québec, Canada, together with aegirine, eudialyte, manganoneptunite, polylithionite, serandite, and steenstrupine-(Ce).[12][13]

Combination of elements in abenakiite-(Ce) is unique. Somewhat chemically similar mineral is steenstrupine-(Ce).[13][14] The hyper-sodium abenakiite-(Ce) is also unique in supposed presence of sulfur dioxide ligand. With a single grain (originally) found, abenakiite-(Ce) is extremely rare.[12]

In the crystal structure, described as a hexagonal net, of abenakiite-(Ce) there are:[12]

- chains of Template:Chem polyhedra, connected with Template:Chem groups

- columns with six-membered rings of Template:Chem, and Template:Chem, and Template:Chem polyhedra (REE - rare earth elements)

- Template:Chem groups, Template:Chem octahedra, and disordered Template:Chem ligands within the columns

Alluaivites

Alluaivite (International Mineralogical Association (IMA) symbol: Aav[11]) is a rare mineral of the eudialyte group,[15] with complex formula written as Template:Chem·2Template:Chem.[16][15] The two dual-nature minerals of the group, being both titano- and zirconosilicates, labyrinthite and dualite, respectively, contain the alluaivite module in their structures.[17][18] Alluaivite is named after Mt. Alluaiv in Lovozero Tundry massif, Kola Peninsula, Russia, where it is found in ultra-agpaitic, hyperalkaline pegmatites.[19][15][16]

Alluaivite contains relatively high amounts of admixing strontium, cerium, potassium, and barium, with lesser amounts of substituting lanthanum and zirconium.[19]

Alluaivite was found in ultra-agpaitic (highly alkaline) pegmatites on Mt. Alluaiv, Lovozero massif, Kola Peninsula, Russia - hence its name.[19] Associating minerals are aegirine, arfvedsonite, eudialyte, nepheline, potassic feldspar, and sodalite.[19] Template:Clear

Beryls

"Beryl of various colors is found most commonly in granitic pegmatites, but also occurs in mica schists ... Goshenite [a beryl clear to white cyclosilicate] is found to some extent in almost all beryl localities."[20]

The gem-gravel placer deposits of Sri Lanka contain aquamarine.

The deep blue version of aquamarine is called maxixe. Maxixe is commonly found in the country of Madagascar. Its color fades to white when exposed to sunlight or is subjected to heat treatment, though the color returns with irradiation.

The pale blue color of aquamarine is attributed to Fe2+. The Fe3+ ions produce golden-yellow color, and when both Fe2+ and Fe3+ are present, the color is a darker blue as in maxixe. Decoloration of maxixe by light or heat thus may be due to the charge transfer Fe3+ and Fe2+.[21][22][23][24] Dark-blue maxixe color can be produced in green, pink or yellow beryl by irradiating it with high-energy particles (gamma rays, neutrons or even X-rays).[25] Template:Clear

Breyites

Breyite has the chemical formula Template:Chem, crystallizes in the triclinic system, is a member of the margarosanite group of minerals, is a polymorph of pseudowollastonite and Wollastonite, and isostructural with margarosanite and walstromite.[26]

Breyite is a cyclosilicate.[27]

Eudialytes

Eudialyte is a somewhat rare, red silicate mineral, which forms in alkaline igneous rocks, such as nepheline syenites. Template:Clear

Margarosanites

Walstromites

Inosilicates

Metasilicates

Def. the "oxyanion of silicon SiO32- or any salt or mineral containing this ion"[28] is called a metasilicate. Template:Clear

Pyroxferroites

The pyroxferroite crystals in the image on the right are 0.6 x 1.1 x 0.7 cm in dimensions. Template:Clear

Raites

"This hydrated sodium-manganese silicate [raite] extends the already wide range of manganese crystal chemistry (3), which includes various complex oxides in ore deposits and nodules from the sea floor and certain farming areas, the pyroxmangite analog of the lunar volcanic metasilicate pyroxferroite, the Mn analog yofortierite of the clay mineral palygorskite, and the unnamed Mn analog of sepiolite."[29] Template:Clear

Wollastonites

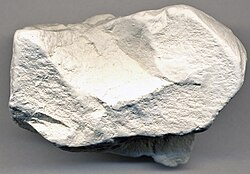

Wollastonite is a calcium metasilicate with the formula Template:Chem.

Wollastonite may contain small amounts of iron, magnesium, and manganese substituting for calcium that is usually white, forms when impure limestone or dolomite is subjected to high temperature and pressure, which sometimes occurs in the presence of silica-bearing fluids as in skarns,[30] or in contact with metamorphic rocks, named after the English chemist and mineralogist William Hyde Wollaston (1766–1828).

Despite its chemical similarity to the compositional spectrum of the pyroxene group of minerals—where magnesium and iron substitution for calcium ends with diopside and hedenbergite respectively—it is structurally very different, with a third Template:Chem tetrahedron[31] in the linked chain (as opposed to two in the pyroxenes).

In a pure Template:Chem, each component forms nearly half of the mineral by weight: 48.3% of CaO and 51.7% of Template:Chem. In some cases, small amounts of iron (Fe), and manganese (Mn), and lesser amounts of magnesium (Mg) substitute for calcium (Ca) in the mineral formula (e.g., rhodonit]).[32] Wollastonite can form a series of solid solutions in the system Template:Chem-Template:Chem, or hydrothermal synthesis of phases in the system Template:Chem-Template:Chem.[31]

Wollastonite usually occurs as a common constituent of a thermally metamorphosed impure limestone, it also could occur when the silicon is due to metamorphism in contact altered calcareous sediments, or to contamination in the invading igneous rock. In most of these occurrences it is the result of the following reaction between calcite and silica with the loss of carbon dioxide:[31]

- CaCO3 + SiO2 → CaSiO3 + CO2

Wollastonite may also be produced in a diffusion reaction in skarn, it develops when limestone within a sandstone is metamorphosed by a dike, which results in the formation of wollastonite in the sandstone as a result of outward migration of Ca.[31]

Associated minerals: garnets, vesuvianite, diopside, tremolite, epidote, plagioclase feldspar, pyroxene and calcite. It is named after the English chemist and mineralogist William Hyde Wollaston (1766–1828).

Wollastonite crystallizes triclinically in space group PTemplate:Overline with the lattice constants a = 7.94 Å, b = 7.32 Å, c = 7.07 Å; α = 90,03°, β = 95,37°, γ = 103,43° and six formula units per unit cell.[33] Wollastonite was once classed structurally among the pyroxene group, because both of these groups have a ratio of Si:O = 1:3. In 1931, Warren and Biscoe showed that the crystal structure of wollastonite differs from minerals of the pyroxene group, and they classified this mineral within a group known as the pyroxenoids.[31] It has been shown that the pyroxenoid chains are more kinked than those of pyroxene group, and exhibit longer repeat distance. The structure of wollastonite contains infinite chains of [[[:Template:Chem]]] tetrahedra sharing common vertices, running parallel to the b-axis. The chain motif in wollastonite repeats after three tetrahedra, whereas in pyroxenes only two are needed. The repeat distance in the wollastonite chains is 7.32 Å and equals the length of the crystallographic b-axis.

Molten CaSiO3, maintains a tetrahedral SiO4 local structure, at temperatures up to 2000 ˚C.[34] The nearest neighbour Ca-O coordination decreases from 6.0(2) in the room temperature glass to 5.0(2) in the 1700 ˚C liquid, coincident with an increasing number of longer Ca-O neighbors.[35][36]

"Primary silicate–melt and carbonate–salt inclusions occur in the phenocrysts (nepheline, fluorapatite, wollastonite, clinopyroxene) in the 1917 eruption combeite–wollastonite nephelinite at Oldoinyo Lengai."[37]

Large deposits of wollastonite have been identified in China, Finland, India, Mexico, and the United States. Smaller, but significant, deposits have been identified in Canada, Chile, Kenya, Namibia, South Africa, Spain, Sudan, Tajikistan, Turkey, and Uzbekistan.[38] Template:Clear

Nesosilicates

Orthosilicates

Phyllosilicates

Def. any "silicate mineral having a crystal structure of parallel sheets of silicate tetrahedra"[39] is called a phyllosilicate. Template:Clear

Ajoites

Ajoite has the chemical formula Template:Chem·3Template:Chem,[40] and minor Mn, Fe and Ca are usually also present in the structure.[41] Ajoite is used as a minor ore of copper.

Ajoite (International Mineralogical Association (IMA) symbol Aj[11]) is a hydrated sodium potassium copper aluminium silicate hydroxide mineral.

Ajoite is a secondary mineral that forms from the oxidation of other secondary copper minerals in copper-rich base metal deposits in massive fracture coatings, in vein fillings, and in vugs. It may form from shattuckite and also it may be replaced by shattuckite.[41]

At the type locality it is associated with shattuckite, conichalcite, quartz, muscovite and pyrite.[42][40]

Ajoite is named after its type locality, the New Cornelia Mine in the Ajo District of Pima County, Arizona. Type specimen material is conserved at the National Museum of Natural History, Washington DC, USA, reference number 113220.

Other localities include Wickenburg and Maricopa County, Arizona, within the United States, and the Messina (Musina) District in South Africa. Quartz specimens from the defunct Messina Mines on the border between Zimbabwe and South Africa are well known for their inclusions of blue copper silicate minerals such as shattuckite, papagoite and ajoite,[43] but ajoite from American localities does not occur like this. Template:Clear

Biotites

Biotite has the chemical formula "K(Mg, Fe)3(Al, Fe)Si3O10(OH, F)2".[44]

Def. a "dark brown mica; it is a mixed aluminosilicate and fluoride of potassium, magnesium and iron"[45] is called a biotite. Template:Clear

Garnierites

Chemical analysis of garnierite samples yields non-stoichiometric formulae that can be reduced to formulas like those of talc and serpentine suggesting a talc monohydrate formula of Template:ChemTemplate:Chem for the talc-like garnierite.[46]

The main difference between the serpentine-like and talc-like variants of garnierite is the spacing between layers in the structure, seen in x-ray powder diffraction studies. The serpentine-like variants have 7 Å basal spacings while the talc-like variants have a basal spacing of 10 Å.[46]

Garnierite is a layer silicate.[46]

7 Å type garnierites usually resemble chrysotile or lizardite in their structures, while 10 Å types usually resemble pimelite.[46]

The color comes from the presence of nickel in the mineral structure for magnesium.[46] Template:Clear

Kaolinites

Kaolinite has the chemical formula Template:Chem.

Kaolinite is a clay mineral, a layered silicate mineral, with one tetrahedral sheet of silica (Template:Chem) linked through oxygen atoms to one octahedral sheet of alumina (Template:Chem) octahedra.[31] Rocks that are rich in kaolinite are known as kaolin or porcelain (china) clay.[47]

The chemical formula for kaolinite as used in mineralogy is Template:Chem,[48] however, in ceramics applications the formula is typically written in terms of oxides, thus the formula for kaolinite is Template:Chem*2Template:Chem*2Template:Chem.[49]

As the most numerous element is oxygen at 9 for 52.9 at %, kaolin is an oxide. Template:Clear

Micas

Def. a group of monoclinic phyllosilicates with the general formula[50]

- X2Y4–6Z8O20(OH,F)4

- in which X is K, Na, or Ca or less commonly Ba, Rb, or Cs;

- Y is Al, Mg, or Fe or less commonly Mn, Cr, Ti, Li, etc.;

- Z is chiefly Si or Al, but also may include Fe3+ or Ti;

- dioctahedral (Y = 4) and trioctahedral (Y = 6)

is called a mica. Template:Clear

Muscovites

Def. a "pale brown mineral of the mica group, being a basic potassium aluminosilicate[51] with the chemical formula KAl2(Si3Al)O10(OH],F)2"[52] is called a muscovite.

"The strongly peraluminous tuffs contain phenocrysts of andalusite, sillimanite, and muscovite and have high 87Sr/86Sri (0.7258 and 0.7226) and δ18O (+11‰). Elevated concentrations of Li, Cs, Be, Sn, B, and other minor elements compare with those in “tin granites.”"[53] Template:Clear

Serpentines

The serpentine subgroup (part of the kaolinite-serpentine group)[54] are greenish, brownish, or spotted minerals commonly found in serpentinite rocks, used as a source of magnesium and asbestos, and as a decorative stone.[55] The name is thought to come from the greenish color being that of a serpent.[56]

The serpentine subgroup are a set of common rock-forming hydroxyl magnesium iron phyllosilicates Template:Chem minerals, resulting from the metamorphism of the minerals that are contained in ultramafic rocks.[57] They may contain minor amounts of other elements including chromium, manganese, cobalt or nickel. In mineralogy and gemology, serpentine may refer to any of 20 varieties belonging to the serpentine subgroup. Owing to admixture, these varieties are not always easy to individualize, and distinctions are not usually made. There are three important mineral polymorphs of serpentine: antigorite, chrysotile and lizardite.

The serpentine subgroup of minerals are polymorphous, meaning that they have the same chemical formulae, but the atoms are arranged into different structures, or crystal lattices.[58] Chrysotile, which has a fiberous habit, is one polymorph of serpentine and is one of the more important asbestos minerals. Other polymorphs in the serpentine subgroup may have a platy habit. Antigorite and lizardite are the polymorphs with platy habit.

Serpentinization is a form of low-temperature metamorphism of ultramafic rocks, such as dunite, harzburgite, or lherzolite. These are rocks low in silica and composed mostly of olivine, pyroxene, and chromite. Serpentinization is driven largely by hydration and oxidation of olivine and pyroxene to serpentine minerals, brucite, and magnetite.[59] Under the unusual chemical conditions accompanying serpentinization, water is the oxidizing agent, and is itself reduced to hydrogen, Template:Chem. This leads to further reactions that produce rare iron group native element minerals, such as awaruite (Template:Chem) and native iron;[60] methane and other hydrocarbon compounds; and hydrogen sulfide.[61]

During serpentinization, large amounts of water are absorbed into the rock, increasing the volume, reducing the density and destroying the original structure.[62][63] The density changes from Template:Convert with a concurrent volume increase on the order of 30-40%.[64] The reaction is highly exothermic and rock temperatures can be raised by about Template:Convert,[63] providing an energy source for formation of non-volcanic hydrothermal vents.[65] The hydrogen, methane, and hydrogen sulfide produced during serpentinization are released at these vents and provide energy sources for deep sea chemotroph microorganisms.[66][63]

The final mineral composition of serpentinite is usually dominated by lizardite, chrysotile, and magnetite. Brucite and antigorite are less commonly present. Lizardite, chrysotile, and antigorite are serpentine minerals. Accessory minerals, present in small quantities, include awaruite, other native metal minerals, and sulfide minerals.[67]

Olivine is a solid solution of forsterite, the magnesium-endmember, and fayalite, the iron-endmember, with forsterite typically making up about 90% of the olivine in ultramafic rocks.[68] Serpentinite can form from olivine via several reactions:

Reaction 1a tightly binds silica, lowering its chemical activity to the lowest values seen in common rocks of the Earth's crust.[69] Serpentinization then continues through the hydration of olivine to yield serpentine and brucite (Reaction 1b).[70] The mixture of brucite and serpentine formed by Reaction 1b has the lowest silica activity in the serpentinite, so that the brucite phase is very important in understanding serpentinization.[69] However, the brucite is often blended in with the serpentine such that it is difficult to identify except with X-ray diffraction, and it is easily altered under surface weathering conditions.[71]

A similar suite of reactions involves pyroxene-group minerals:

Reaction 2a quickly comes to a halt as silica becomes unavailable, and Reaction 2b takes over.[72] When olivine is abundant, silica activity drops low enough that talc begins to react with olivine:

This reaction requires higher temperatures than those at which brucite forms.[73]

The final mineralogy depends both on rock and fluid compositions, temperature, and pressure. Antigorite forms in reactions at temperatures that can exceed Template:Convert during metamorphism, and it is the serpentine group mineral stable at the highest temperatures. Lizardite and chrysotile can form at low temperatures very near the Earth's surface.[74]

Ultramafic rocks often contain calcium-rich pyroxene (diopside), which breaks down according to the reaction

This raises both the pH, often to very high values, and the calcium content of the fluids involved in serpentinization. These fluids are highly reactive and may transport calcium and other elements into surrounding mafic rocks. Fluid reaction with these rocks may create metasomatic reaction zones enriched in calcium and depleted in silica, called rodingites.[75]

In most crustal rock, the chemical activity of oxygen is prevented from dropping to very low values by the fayalite-magnetite-quartz (FMQ) buffer.[76] The very low chemical activity of silica during serpentinization eliminates this buffer, allowing serpentinization to produce highly reducing conditions.[69] Under these conditions, water is capable of oxidizing ferrous (Template:Chem) ions in fayalite. The process is of interest because it generates hydrogen gas:[77][78]

However, studies of serpentinites suggest that iron minerals are first converted to ferroan brucite, Template:Chem,[79] which then undergoes the Schikorr reaction in the anaerobic conditions of serpentinization:[80][81]

Maximum reducing conditions, and the maximum rate of production of hydrogen, occur when the temperature of serpentinization is between Template:Convert.[82] If the original ultramafic rock (the protolith) is peridotite, which is rich in olivine, considerable magnetite and hydrogen are produced. When the protolith is pyroxenite, which contains more pyroxene than olivine, iron-rich talc is produced with no magnetite and only modest hydrogen production. Infiltration of silica-bearing fluids during serpentinization can suppress both the formation of brucite and the subsequent production of hydrogen.[83]

Chromite present in the protolith will be altered to chromium-rich magnetite at lower serpentinization temperatures. At higher temperatures, it will be altered to iron-rich chromite (ferrit-chromite).[84] During serpentinization, the rock is enriched in chlorine, boron, fluorine, and sulfur. Sulfur will be reduce to hydrogen sulfide and sulfide minerals, though significant quantities are incorporated into serpentine minerals, and some may later be reoxidized to sulfate minerals such as anhydrite.[64] The sulfides produced include nickel-rich sulfides, such as mackinawite.[85]

Laboratory experiments have confirmed that at a temperature of Template:Convert and pressure of 500 bars, olivine serpentinizes with release of hydrogen gas. In addition, methane and complex hydrocarbons are formed through reduction of carbon dioxide. The process may be catalyzed by magnetite formed during serpentinization.[61] One reaction pathway is:[80]

Lizardite and chrysotile are stable at low temperatures and pressures, while antigorite is stable at higher temperatures and pressure. Its presence in a serpentinite indicates either that serpentinization took place at unusually high pressure and temperature or that the rock experienced higher grade metamorphism after serpentinization was complete.[86]

Infiltration of Template:Chem-bearing fluids into serpentinite causes distinctive talc-carbonate alteration. Brucite rapidly converts to magnesite and serpentine minerals (other than antigorite) are converted to talc. The presence of pseudomorphs of the original serpentinite minerals shows that this alteration takes place after serpentinization.[87]

Serpentinite may contain chlorite, tremolite, and metamorphic olivine and diopside. This indicates that the serpentinite has been subject to more intense metamorphism, reaching the upper greenschist or amphibolite metamorphic facies.[88]

Above about Template:Convert, antigorite begins to break down. Thus serpentinite does not exist at higher metamorphic facies.[66] Template:Clear

Sorosilicates

Tectosilicates

Def. any "of various silicate minerals ... with a three-dimensional framework of silicate tetrahedra"[89] is called a tectosilicate.

Def. type "of silicate crystal structure characterized by the sharing of all SiO4 tetrahedral oxygens resulting in three-dimensional framework structures"[44] is called a tektosilicate. Template:Clear

Quartzes

Red "thermoluminescence (RTL) emission from quartz, as a dosimeter for baked sediments and volcanic deposits, [from] older (i.e., >1 Ma), quartz-bearing known age volcanic deposits [can use as standards] independently-dated silicic volcanic deposits from New Zealand, ranging in age from 300 ka through to 1.6 Ma."[90] Template:Clear

Alpha quartzes

Def. "a continuous framework [tectosilicate] of SiO4 silicon–oxygen tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tetrahedra, giving an overall [chemical] formula [of] SiO2 ... [of] trigonal trapezohedral class 3 2"[91], usually with some substitutional or interstitial impurities, is called α-quartz.

Alpha-quartz (space group P3121, no. 152, or P3221, no. 154) under a high pressure of 2-3 gigapascals and a moderately high temperature of 700°C changes space group to monoclinic C2/c, no. 15, and becomes the mineral coesite. It is "found in extreme conditions such as the impact craters of meteorites.

When the concentration of interstitial or substitutional impurities becomes sufficient to change the space group of a mineral such as α-quartz, the result is another mineral. When the physical conditions are sufficient to change the solid space group of α-quartz without changing the chemical composition or formula, another mineral results.

Referring to the image on the right: "Lake County experienced incredible volcanic activity. The heat melted the quartz but temperatures and pressures were just right so it was not destroyed. Rather, the melted quartz was carried along with the lava flows."[92]

"Shocked quartz is associated with two high pressure polymorphs of silicon dioxide: coesite and stishovite. These polymorphs have a crystal structure different from standard quartz. Again, this structure can only be formed by intense pressure, but moderate temperatures. High temperatures would anneal the quartz back to its standard form."[93]

"Short-lived bottle-green or blue luminescence colours with zones of non-luminescing bands are very common in authigenic quartz overgrowths, fracture fillings or idiomorphic vein crystals. Dark brown, short-lived yellow or pink colours are often found in quartz replacing sulphate minerals. Quartz from tectonically active regions commonly exhibits a brown luminescence colour. A red luminescence colour is typical for quartz crystallized close to a volcanic dyke or sill."[94]

So far several of the polymorphs of α-quartz formed at high temperature and pressure occur with rock types away from meteorite impact craters.

At lower right is a thin section through a sand-sized quartz grain "from the USGS-NASA Langley core showing two well-developed, intersecting sets of shock lamellae produced by the late Eocene Chesapeake Bay bolide impact. This shocked quartz grain is from the upper part of the crater-fill deposits at a depth of 820.6 ft in the core. The corehole is located at the NASA Langley Research Center, Hampton, VA, near the southwestern margin of the Chesapeake Bay impact crater."[95] "Very high pressures produced by strong shock waves cause dislocations in the crystal structure of quartz grains along preferred orientations. These dislocations appear as sets of parallel lamellae in the quartz when viewed with a petrographic microscope. Bolide impacts are the only natural process known to produce shock lamellae in quartz grains."[95]

At third down on the right shows another thin section in plane polarized light of a shocked quartz grain with two sets of decorated planar deformation features (PDFs) surrounded by a cryptocrystalline matrix from the Suvasvesi South impact structure, Finland.

In a specimen of shocked quartz, stishovite can be separated from quartz by applying hydrogen fluoride (HF); unlike quartz, stishovite will not react.[96]

The major evidence for a volcanic origin for tektites "includes: close analogy between shaped tektites and small volcanic bombs, and between layered tektites and lava or tuff-lava flows or huge bombs; analogy between flanged tektites and volcanic bombs ablated by gasjets: long-time, multistage formation of some tektites that corresponds to wide variations in their radiometric ages; well-ordered long compositional trends (series) typical of magmatic differentiation; different compositional tektite families (subseries) comparable to different stages (phases) of the volcanic process."[97]

"As with the North American microtektite-bearing cores, all the Australasian microtektite-bearing cores containing coesite and shocked quartz also contained volcanic ash, which complicated the search."[98] Template:Clear

Beta quartzes

Beta quartz (β-Quartz) is stable "between 573° and 870°C".[44]

Coesites

Coesite is a polymorph of silicon dioxide Template:Chem that is formed when very high pressure (2–3 gigapascals), and moderately high temperature (Template:Convert), are applied to quartz. Coesite was first synthesized by Loring Coes Jr., a chemist at the Norton Company, in 1953.[99][100]

In 1960, a natural occurrence of coesite was reported by Edward C. T. Chao,[101] in collaboration with Eugene Shoemaker, from the Barringer Crater, in Arizona, US, which was evidence that the crater must have been formed by an impact. After this report, the presence of coesite in unmetamorphosed rocks was taken as evidence of a meteorite impact event or of an atomic bomb explosion. It was not expected that coesite would survive in high pressure metamorphic rocks.

In metamorphic rocks, coesite was initially described in eclogite xenoliths from the mantle of the Earth that were carried up by ascending magmas; kimberlite is the most common host of such xenoliths.[102] In metamorphic rocks, coesite is now recognized as one of the best mineral indicators of metamorphism at very high pressures (UHP, or ultrahigh-pressure metamorphism).[103] Such UHP metamorphic rocks record subduction or continental collisions in which crustal rocks are carried to depths of Template:Convert or more. Coesite is formed at pressures above about 2.5 GPa (25 kbar) and temperature above about 700 °C. This corresponds to a depth of about 70 km in the Earth. It can be preserved as mineral inclusions in other phases because as it partially reverts to quartz, the quartz rim exerts pressure on the core of the grain, preserving the metastable grain as tectonic forces uplift and expose these rock at the surface. As a result, the grains have a characteristic texture of a polycrystalline quartz rim.

Coesite has been identified in UHP metamorphic rocks around the world, including the western Alps of Italy at Dora Maira,[103] the Erzgebirge of Germany,[104] the Lanterman Range of Antarctica,[105] in the Kokchetav Massif of Kazakhstan,[106] in the Western Gneiss region of Norway,[107] the Dabie-Shan Range in Eastern China,[108] the Himalayas of Eastern Pakistan,[109] and the Vermont Appalachian Mountains.[110][111]

Coesite is a tectosilicate with each silicon atom surrounded by four oxygen atoms in a tetrahedron. Each oxygen atom is then bonded to two Si atoms to form a framework. There are two crystallographically distinct Si atoms and five different oxygen positions in the unit cell. Although the unit cell is close to being hexagonal in shape ("a" and "c" are nearly equal and β nearly 120°), it is inherently monoclinic and cannot be hexagonal. The crystal structure of coesite is similar to that of feldspar and consists of four silicon dioxide tetrahedra arranged in Template:Chem and Template:Chem rings. The rings are further arranged into chains. This structure is metastable within the stability field of quartz: coesite will eventually decay back into quartz with a consequent volume increase, although the metamorphic reaction is very slow at the low temperatures of the Earth's surface. The crystal symmetry is monoclinic C2/c, No.15, Pearson symbol mS48.[112] Template:Clear

Cristobalites

Def. a high-temperature (above 1470°C) polymorph of α-quartz with cubic, FdTemplate:Overlinem, space group no. 227, and a tetragonal form (P41212, space group no. 92) is called cristobalite.

Def. a "mineral of volcanic rocks that solidified at a high temperature [...] chemically identical to quartz, with the chemical formula SiO2, but has a different crystal structure"[113] is called cristobalite.

There is more than one form of the cristobalite framework. At high temperatures, the structure is called β-cristobalite. It is in the cubic crystal system, space group FdTemplate:Overlinem (No. 227, Pearson symbol cF104).[114] It has the diamond structure but with linked tetrahedra of silicon and oxygen where the carbon atoms are in diamond. A chiral tetragonal form called α-cristobalite (space group either P41212, No. 92,[115] or P43212, No. 96, at random) occurs on cooling below about 250 °C at ambient pressure and is related to the cubic form by static tilting of the silica tetrahedra in the framework. This transition is variously called the low-high or transition. It may be termed "displacive"; i.e., it is not generally possible to prevent the cubic β-form from becoming tetragonal by rapid cooling. Under rare circumstances the cubic form may be preserved if the crystal grain is pinned in a matrix that does not allow for the considerable spontaneous strain that is involved in the transition, which causes a change in shape of the crystal. This transition is highly discontinuous. Going from the α form to the β form causes an increase in volume of 3[116] or 4[117] percent. The exact transition temperature depends on the crystallinity of the cristobalite sample, which itself depends on factors such as how long it has been annealed at a particular temperature.

The cubic β phase consists of dynamically disordered silica tetrahedra. The tetrahedra remain fairly regular and are displaced from their ideal static orientations due to the action of a class of low-frequency phonons called rigid unit modes. It is the "freezing" of one of these rigid unit modes that is the soft mode for the α–β transition.

In β-cristobalite, there are right-handed and left-handed helices of tetrahedra (or of silicon atoms) parallel to all three axes. But in the α–β phase transition, only the right-handed or the left-handed helix in one direction is preserved (the other becoming a two-fold screw axis), so only one of the three degenerate cubic crystallographic axes retains a fourfold rotational axis (actually a screw axis) in the tetragonal form. (That axis becomes the "c" axis, and the new "a" axes are rotated 45° compared to the other two old axes. The new "a" lattice parameter is shorter by approximately the square root of 2, so the α unit cell contains only 4 silicon atoms rather than 8.) The choice of axis is arbitrary, so that various twins can form within the same grain. These different twin orientations coupled with the discontinuous nature of the transition (volume and slight shape change) can cause considerable mechanical damage to materials in which cristobalite is present and that pass repeatedly through the transition temperature, such as refractory bricks.

When devitrifying silica, cristobalite is usually the first phase to form, even when well outside its thermodynamic stability range. This is an example of Ostwald's step rule. The dynamically disordered nature of the β-phase is partly responsible for the low enthalpy of fusion of silica.

The micrometre-scale spheres that make up precious opal exhibit some x-ray diffraction patterns that are similar to that of cristobalite, but lack any long-range order so they are not considered true cristobalite. In addition, the presence of structural water in opal makes it doubtful that opal consists of cristobalite.[118][119] Template:Clear

Stishovites

Stishovite is an extremely hard, dense tetragonal polymorph of silicon dioxide. It is very rare on the Earth's surface; however, it may be a predominant form of silicon dioxide in the Earth, especially in the lower mantle.[120]

Stishovite was named after Sergey M. Stishov, a Russian high-pressure physicist who first synthesized the mineral in 1961. It was discovered in Meteor Crater in 1962 by Edward C. T. Chao.[121]

Unlike other silica polymorphs, the crystal structure of stishovite resembles that of rutile Template:Chem. The silicon in stishovite adopts an octahedral coordination geometry, being bound to six oxides. Similarly, the oxides are three-connected, unlike low-pressure forms of SiO2. In most silicates, silicon is tetrahedral, being bound to four oxides.[122] It was long considered the hardest known oxide (~30 GPa Vickers[123]); however, boron suboxide has been discovered[124] in 2002 to be much harder. At normal temperature and pressure, stishovite is metastable.

Stishovite can be separated from quartz by applying hydrogen fluoride (HF); unlike quartz, stishovite will not react.[121]

Large natural crystals of stishovite are extremely rare and are usually found as clasts of 1 to 2 mm in length. When found, they can be difficult to distinguish from regular quartz without laboratory analysis. It has a vitreous luster, is transparent (or translucent), and is extremely hard. Stishovite usually sits as small rounded gravels in a matrix of other minerals.

Until recently, the only known occurrences of stishovite in nature formed at the very high shock pressures (>100 kbar, or 10 GPa) and temperatures (> 1200 °C) present during hypervelocity meteorite impact into quartz-bearing rock. Minute amounts of stishovite have been found within diamonds,[125] and post-stishovite phases were identified within ultra-high-pressure mantle rocks.[126] Stishovite may also be synthesized by duplicating these conditions in the laboratory, either isostatically or through shock (see shocked quartz).[127] At 4.287 g/cm3, it is the second densest polymorph of silica, after seifertite. It has tetragonal crystal symmetry, P42/mnm, No. 136, Pearson symbol tP6.[128] Template:Clear

Def. a polymorph of α-quartz formed by pressures > 100 kbar or 10 GPa and temperatures > 1200 °C is called stishovite.[129]

Stishovite may be formed by an instantaneous over pressure such as by an impact or nuclear explosion type event.[93]

Minute amounts of stishovite has been found within diamonds.[125] Template:Clear

Tridymites

Def. a polymorph of α-quartz formed at temperatures from 22-460°C with at least seven space groups for its forms with tabular crystals is called tridymite.[130]

Def. a "rare [tektosilicate] mineral of volcanic rocks that solidified at a high temperature, [with the chemical composition of silicon dioxide, SiO22,] chemically identical to quartz, but has a different crystal structure"[131] is called a tridymite.

Tridymite is a high-temperature polymorph of silica and usually occurs as minute tabular white or colorless pseudo-hexagonal crystals, or scales, in cavities in felsic volcanic rocks. Its chemical formula is Template:Chem. Tridymite was first described in 1868 and the type location is in Hidalgo, Mexico. The name is from the Greek tridymos for triplet as tridymite commonly occurs as twinned crystal trillings[132] (compound crystals comprising three twinned crystal components).

α-tridymite is orthorhomic and β-tridymite is hexagonal.[44]

Tridymite can occur in seven crystalline forms. Two of the most common at standard pressure are known as α and β. The α-tridymite phase is favored at elevated temperatures (>870 °C) and it converts to β-cristobalite at 1470 °C.[133][31] However, tridymite does usually not form from pure β-quartz, one needs to add trace amounts of certain compounds to achieve this.[134] Otherwise the β-quartz-tridymite transition is skipped and β-quartz transitions directly to cristobalite at 1050 °C without occurrence of the tridymite phase.

| Name | Symmetry | Space group | T (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HP (β) | Hexagonal | P63/mmc | 460 |

| LHP | Hexagonal | P6322 | 400 |

| OC (α) | Orthorhombic | C2221 | 220 |

| OS | Orthorhombic | 100–200 | |

| OP | Orthorhombic | P212121 | 155 |

| MC | Monoclinic | Cc | 22 |

| MX | Monoclinic | C1 | 22 |

In the table, M, O, H, C, P, L and S stand for monoclinic, orthorhombic, hexagonal, centered, primitive, low (temperature) and superlattice. T indicates the temperature, at which the corresponding phase is relatively stable, though the interconversions between phases are complex and sample dependent, and all these forms can coexist at ambient conditions.[135] Mineralogy handbooks often arbitrarily assign tridymite to the triclinic crystal system, yet use hexagonal Miller indices because of the hexagonal crystal shape (see infobox image).[132] Template:Clear

Feldspars

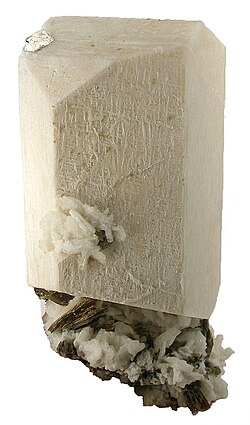

Def. a group of "aluminum silicates [aluminosilicates] of the alkali metals sodium, potassium, calcium and barium"[136] are called feldspars, or feldspar.

"Feldspar is by far the most abundant group of minerals in the earth's crust, forming about 60% of terrestrial rocks."[137]

"The mineralogical composition of most feldspars can be expressed in terms of the ternary system Orthoclase (KAlSi3O8), Albite (NaAlSi3O8) and Anorthite (CaAl2Si2O8)."[137]

"The minerals of which the composition is comprised between Albite and Anorthite are known as the plagioclase feldspars, while those comprised between Albite and Orthoclase are called the alkali feldspars due to the presence of alkali metals sodium and potassium."[137] Template:Clear

Albites

Albite (International Mineralogical Association (IMA) symbol: Ab[11]) is a plagioclase feldspar mineral, is the sodium endmember of the plagioclase solid solution series, represents a plagioclase with less than 10% anorthite content. The pure albite endmember has the formula Template:Chem, a tectosilicate, is usually pure white, hence its name from Latin, Template:Lang,[138] and is a common constituent in felsic rocks. The almost end member has the chemical formula Template:Chem.[139]

There are two variants of albite, which are referred to as 'low albite' and 'high albite'; the latter is also known as 'analbite'. Although both variants are triclinic, they differ in the volume of their unit cell, which is slightly larger for the 'high' form. The 'high' form can be produced from the 'low' form by heating above Template:Convert[140] High albite can be found in meteor impact craters such as in Winslow, Coconino Co., Arizona, United States.[141] Upon further heating to more than Template:Convert the crystal symmetry changes from triclinic to monoclinic; this variant is also known as 'monalbite'.[142] Albite melts at Template:Convert.[143]

Albites occur in granitic and pegmatite masses (often as the variety Cleavelandite),[144] in some hydrothermal vein deposits, and forms part of the typical greenschist metamorphic facies for rocks of originally basaltic composition. Minerals that albite is often considered associated with in occurrence include biotite, hornblende, orthoclase, muscovite and quartz.[145]

Occurrence: "A major constituent of granites and granite pegmatites, alkalic diorites, basalts, and in hydrothermal and alpine veins. A product of potassium metasomatism and in low-temperature and low-pressure metamorphic facies and in some schists. Detrital and authigenic in sedimentary rocks."[139]

Polymorphs: Kumdykolite, Lingunite.[145]

Structural modifications: "Low- and high-temperature structural modifications exist ('low albite' and 'high albite'), with ordered and disordered Al-Si distribution, respectively."[145]

"The Na-rich end member of the Albite-Anorthite Series (= Plagioclase)."[145]

Empirical formula: Template:Chem.[146]

Anorthites

Anorthites have the chemical formula Template:Chem.[147]

Anorthite is rare on the Earth[50] but abundant on the Moon.[148]

Anorthite is a rare compositional variety of plagioclase that occurs in mafic igneous rock, also occurs in metamorphic rocks of granulite facies, in metamorphosed carbonate rocks, and corundum deposits,[149] type localities are Monte Somma and Valle di Fassa, Italy. It was first described in 1823,[150] more rare in surficial rocks than it normally would be due to its high weathering potential in the Goldich dissolution series.

It also makes up much of the lunar highlands; the Genesis Rock, collected during the 1971 Apollo 15 mission, is made of anorthosite, a rock composed largely of anorthite. Anorthite was discovered in samples from comet Wild 2, and the mineral is an important constituent of Ca-Al-rich inclusions in rare varieties of chondritic meteorites. Template:Clear

Anorthoclases

When potassium replaces the sodium characteristic in albite at amounts of up to 10%, the mineral is then considered to be anorthoclase.[151]

Oligoclases

"The apical parts of large volcanoes along the East Pacific Rise (islands and seamounts) are encrusted with rocks of the alkali volcanic suite (alkali basalt, andesine- and oligoclase-andesite, and trachyte)."[152] Template:Clear

Orthoclases

"The mineralogical composition of most feldspars can be expressed in terms of the ternary system Orthoclase (KAlSi3O8), Albite (NaAlSi3O8) and Anorthite (CaAl2Si2O8)."[137]

"The minerals of which the composition is comprised between Albite and Anorthite are known as the plagioclase feldspars, while those comprised between Albite and Orthoclase are called the alkali feldspars due to the presence of alkali metals sodium and potassium."[137]

"Volcanic rock fragments, feldspar (orthoclase, andesine, and rare sanidine), and small amounts of quartz, biotite, and hornblende make up the bulk of these rocks."[153] Template:Clear

Plagioclases

Def. "[a]ny of a group of aluminum silicate feldspathic minerals ranging in their ratio of calcium to sodium"[154] is called plagioclase.

Plagioclase is a series of tectosilicate minerals within the feldspar group with a specific chemical composition: Template:Chem – Template:Chem. Plagioclase in hand samples is often identified by its polysynthetic crystal twinning or 'record-groove' effect.

Feldspathoids

Def. any of a group of silicates "that did not contain enough silica to satisfy all the chemical bonds"[155] of the framework is called a feldspathoid.

Volcanic sources that have a low silica concentration are more likely to produce feldspathoid-containing rocks than feldspar-containing rocks.

Feldspathoid volcanic rocks occur in "a suite of basanites, olivine nephelinites, and olivine melilite nephelinites from the Raton-Clayton volcanic field, New Mexico."[156]

"Volcanism in the Raton-Clayton field commenced approximately 7.5 Ma ago with the eruption of alkali basalts and continued intermittently until at least 10,000 y.a. with the eruption of the Capulin Mountain silicic alkalic basalt (Stormer 1972a; Baldwin and Muehlberger 1959). The entire volcanic sequence was erupted onto the high plains east of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, and as such, represents the eastern limit of late Cenozoic volcanism in the western U.S. Volcanic activity in the Raton-Clayton field was contemporaneous with volcanism in the Rio Grande rift, and the Raton-Clayton volcanic field is interpreted as part of the Rio Grande rift system."[156] Template:Clear

Kalsilites

Def. "a rare mineral, a form of KAlSiO4, found in volcanic rocks in parts of Italy"[157] is called a kaliophilite.

Kalsilite (Template:Chem) is a vitreous white to grey feldspathoid that is found in some potassium-rich lavas, such as from Chamengo Crater in Uganda that has a relative Mohs hardness of 5.5.

"Kaliophilite [occurs in] blocks of biotite-pyroxenite volcanic ejecta from Mte. Somma, Vesuvius."[158] Template:Clear

Nephelines

Def. a (Na,K)AlSiO4 "feldspathoid mineral of silica-poor igneous, plutonic and volcanic rocks"[159] is called a nepheline. Template:Clear

Quadridavynes

Def. a feldspathoid, tektosilicate "mineral found in volcanic ash"[160], chemical formula Na6Ca2Si6Al6O24Cl4, is called a quadridavyne.

Quadridavyne is a tektosilicate (feldspathoid), chemical formula Na6Ca2Si6Al6O24Cl4, with a type locality of Ottaviano, Monte Somma, Somma-Vesuvius Complex, Naples Province, Campania, Italy.[161] Template:Clear

Zeolites

The zeolite structural group (Nickel-Strunz classification) includes:[162][163][164][165][166]

- 09.GA. - Zeolites with T5O10 units (T = combined Si and Al) – the fibrous zeolites

- Natrolite framework (NAT): gonnardite, natrolite, mesolite, paranatrolite, scolecite, tetranatrolite

- Edingtonite framework (EDI): edingtonite, kalborsite

- Thomsonite framework (THO): thomsonite-series

- 09.GB. - Chains of single connected 4-membered rings

- Analcime framework (ANA): analcime, leucite, pollucite, wairakite

- Laumontite (LAU), yugawaralite (YUG), goosecreekite (GOO), montesommaite (MON)

- 09.GC. - Chains of doubly connected 4-membered rings

- Phillipsite framework (PHI): harmotome, phillipsite-series

- Gismondine framework (GIS): amicite, gismondine, garronite, gobbinsite

- Boggsite (BOG), merlinoite (MER), mazzite-series (MAZ), paulingite-series (PAU), perlialite (Linde type L framework, zeolite L, LTL)

- 09.GD. - Chains of 6-membered rings – tabular zeolites

- Chabazite framework (CHA): chabazite-series, herschelite, willhendersonite and SSZ-13

- Faujasite framework (FAU): faujasite-series, Linde type X (zeolite X, X zeolites), Linde type Y (zeolite Y, Y zeolites)

- Mordenite framework (MOR): maricopaite, mordenite

- Offretite–wenkite subgroup 09.GD.25 (Nickel–Strunz, 10 ed): offretite (OFF), wenkite (WEN)

- Bellbergite (TMA-E, Aiello and Barrer; framework type EAB), bikitaite (BIK), erionite-series (ERI), ferrierite (FER), gmelinite (GME), levyne-series (LEV), dachiardite-series (DAC), epistilbite (EPI)

- 09.GE. - Chains of T10O20 tetrahedra (T = combined Si and Al)

- Heulandite framework (HEU): clinoptilolite, heulandite-series

- Stilbite framework (STI): barrerite, stellerite, stilbite-series

- Brewsterite framework (BRE): brewsterite-series

- Others

- Cowlesite, pentasil (also known as ZSM-5, framework type MFI), tschernichite (beta polymorph A, disordered framework, BEA), Linde type A framework (zeolite A, LTA)

Analcites

The image on the right contains analcime, or analcite, as colorless sharply formed undamaged crystals to 25 mm in diameter on a 78 mm x 65 mm x 53 mm matrix. They are associated with numerous black prismatic terminated crystals of aegirine, as well as smaller colorless prismatic terminated crystals of natrolite, these from 3 mm to 10 mm in length. Aegirine is a pyroxene. Natrolite is another feldspathoid like analcime of the zeolite group.

Def. a "mineral, a sodium aluminosilicate [with a chemical formula NaAlSi2O6·H2O,][167] having a zeolite structure, found in alkaline basalts"[168] is called an analcime. Template:Clear

Barrerites

Barrerite can have the chemical formula Na4Al4Si14O36•13(H2O).[169]

"Ca may be calcium and/or potassium."[170] Barrerite can have the chemical formula K4Al4Si14O36•13(H2O).[170]

Def. a "white to pinkish tectosilicate zeolite mineral"[171] is called a barrerite. Template:Clear

Leucites

Def. a feldspathoid "mineral of silica-poor igneous, plutonic and volcanic rocks"[172] is called a leucite. Template:Clear

Natrolites

Natrolite is another feldspathoid like analcime of the zeolite group.

"Occurs chiefly in cavities in basalt".[44]

Def. a "fibrous zeolite mineral, being a sodium aluminosilicate,[173] of the chemical formula Na2Al2Si3O10·2H2O"[174] is called a natrolite. Template:Clear

Stellerites

Stellerite has the chemical formula CaAl2Si7O18•7(H2O).[175]

Def. a "hydrated calcium aluminosilicate zeolite, similar to stilbite"[176] is called a stellerite. Template:Clear

Stilbites

Stilbite (Desmine), a zeolite group, has the chemical formula NaCa2Al5Si13O36•16(H2O).[44]

Def. a "tectosilicate zeolite mineral consisting of hydrated calcium aluminium silicate, common in volcanic rocks"[177] is called a stilbite.

Stilbite-Na can have the chemical formula Na3Ca3Al8Si28O72•30(H2O).[178]

Stilbite-Ca can have the chemical formula NaCa4Al8Si28O72•30(H2O).[179] Template:Clear

Hypotheses

- Most minerals on Earth are oxides.

See also

- Aluminide minerals

- Boronide minerals

- Geomineral carbonates

- Geomineral crystallogens

- Geomineral halogens

- Geomineral hydroxides

- Geomineral nickels

- Geomineral oxidanes

- Geomineral silicates

- Geomineral sulfates

- Geomineral sulfides

- Silicate chemicals

- Silicate minerals

- Siliconide minerals

References

External links

Template:Geology resourcesTemplate:Sisterlinks

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 McDonald, A.M., Chao, G.Y., and Grice, J.D., 1994. Abenakiite-(Ce), a new silicophosphate carbonate mineral from Mont Saint-Hilaire, Quebec: Description and structure determination. The Canadian Mineralogist 32, 843-854

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Mindat, Abenakiite-(Ce), Mindat.org

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 http://www.mindat.org/show.php?id=141&ld=2 Mindat

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Khomyakov A. P., Netschelyustov G. N. and Rastsvetaeva R. K. 1990: Alluaivite Template:Chem·2Template:Chem - A new titanosilicate mineral of eudialyte-like structure. Zapiski Vsesoyuznogo Mineralogicheskogo Obshchestva, 119(3), 117-120, in Jambor J. L. and Puziewicz J. 1991: New mineral names. American Mineralogist, 76, 1728-1735; [1]

- ↑ Khomyakov, A.P., Nechelyustov, G.N., and Rastsvetaeva, R.K., 2006. Labyrinthite Template:Chem, a new mineral with a modular eudialyte-like structure from Khibiny Alkaline Massif, Kola Peninsula, Russia. Zapiski Vserossiyskogo Mineralogicheskogo Obshchestva 135(2), 38-49

- ↑ Khomyakov, A.P., Nechelyustov, G.N., and Rastsvetaeva, R.K., 2009: Dualite, Template:Chem, a new zircono-titanosilicate with a modular eudialyte-like structure from the Lovozero alkaline Pluton, Kola Peninsula, Russia. Geology of Ore Deposits 50(7), 574-582

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 http://www.handbookofmineralogy.org/pdfs/Alluaivite.PDF Handbook of Mineralogy

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 31.5 31.6 31.7 Template:Cite book

- ↑ Andrews, R. W. Wollastonite. London, Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1970.

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Wollastonite, USGS Mineral Commodity Summaries 2017

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Ajoite. Handbook of Mineralogy. Retrieved on 2011-10-09.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Gaines, et al (1997) Dana's New Mineralogy, Eighth Edition. Wiley

- ↑ Ajoite. Mindat.org (2011-08-16). Retrieved on 2011-10-09.

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 44.4 44.5 Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 46.3 46.4 Brindley, G.W. and Hang, P.T. (1973) The nature of garnierites – I Structures, chemical compositions and color characteristics. Clays and Clay Minerals, 21, 27-40.

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Deer, W. A., R. A. Howie and J. Zussman (1966) An Introduction to the Rock Forming Minerals, Longman, Template:ISBN

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Serpentine, American Heritage Dictionary

- ↑ Rudler, Frederick William (1911). "Serpentine" . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 675–677.

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Moody, Judith B. (April 1976). "Serpentinization: a review". Lithos. 9 (2): 125–138. Bibcode:1976Litho...9..125M. doi:10.1016/0024-4937(76)90030-X.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Moody, Judith B. (April 1976). "Serpentinization: a review". Lithos. 9 (2): 125–138. Bibcode:1976Litho...9..125M. doi:10.1016/0024-4937(76)90030-X.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 63.2 Serpentinization: The heat engine at Lost City and sponge of the oceanic crust

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Moody, Judith B. (April 1976). "Serpentinization: a review". Lithos. 9 (2): 125–138. Bibcode:1976Litho...9..125M. doi:10.1016/0024-4937(76)90030-X.

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 69.2 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Moody, Judith B. (April 1976). "Serpentinization: a review". Lithos. 9 (2): 125–138. Bibcode:1976Litho...9..125M. doi:10.1016/0024-4937(76)90030-X.

- ↑ Frost, B. R.; Beard, J. S. (3 April 2007). "On Silica Activity and Serpentinization". Journal of Petrology. 48 (7): 1351–1368. doi:10.1093/petrology/egm021.

- ↑ Moody, Judith B. (April 1976). "Serpentinization: a review". Lithos. 9 (2): 125–138. Bibcode:1976Litho...9..125M. doi:10.1016/0024-4937(76)90030-X.

- ↑ Moody, Judith B. (April 1976). "Serpentinization: a review". Lithos. 9 (2): 125–138. Bibcode:1976Litho...9..125M. doi:10.1016/0024-4937(76)90030-X.

- ↑ Frost, B. R.; Beard, J. S. (3 April 2007). "On Silica Activity and Serpentinization". Journal of Petrology. 48 (7): 1351–1368. doi:10.1093/petrology/egm021.

- ↑ Moody, Judith B. (April 1976). "Serpentinization: a review". Lithos. 9 (2): 125–138. Bibcode:1976Litho...9..125M. doi:10.1016/0024-4937(76)90030-X.

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Moody, Judith B. (April 1976). "Serpentinization: a review". Lithos. 9 (2): 125–138. Bibcode:1976Litho...9..125M. doi:10.1016/0024-4937(76)90030-X.

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Moody, Judith B. (April 1976). "Serpentinization: a review". Lithos. 9 (2): 125–138. Bibcode:1976Litho...9..125M. doi:10.1016/0024-4937(76)90030-X.

- ↑ Moody, Judith B. (April 1976). "Serpentinization: a review". Lithos. 9 (2): 125–138. Bibcode:1976Litho...9..125M. doi:10.1016/0024-4937(76)90030-X.

- ↑ Moody, Judith B. (April 1976). "Serpentinization: a review". Lithos. 9 (2): 125–138. Bibcode:1976Litho...9..125M. doi:10.1016/0024-4937(76)90030-X.

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 95.0 95.1 Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ The word "coesite" is pronounced as "Coze-ite" after chemist Loring Coes Jr. Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 103.0 103.1 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Dmitry L. Lakshtanov "The post-stishovite phase transition in hydrous alumina-bearing Template:Chem in the lower mantle of the earth" PNAS 2007 104 (34) 13588-13590; doi:10.1073/pnas.0706113104.

- ↑ 121.0 121.1 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal and references therein

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 125.0 125.1 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ 132.0 132.1 Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ 137.0 137.1 137.2 137.3 137.4 Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ 139.0 139.1 http://rruff.geo.arizona.edu/doclib/hom/albite.pdf Handbook of Mineralogy

- ↑ O.F. Tuttle, N.L. Bowen (1950): High-temperature albite and contiguous feldspars. J. Geol. 58(5), 572–583, https://www.jstor.org/stable/30068571

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Monalbite on Mindat

- ↑ J.P. Greenwood, P.C. Hess (1998): Congruent melting of albite: theory and experiment. J. Geophysical Research. 103(B12), 29815-29828

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ 145.0 145.1 145.2 145.3 Template:Cite web

- ↑ [2] Albie Mineral Data

- ↑ [3] Anorthite}}

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Handbook of Mineralogy

- ↑ Webmineral

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ 156.0 156.1 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 170.0 170.1 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal