WikiJournal Preprints/24-cell: Difference between revisions

imported>Dc.samizdat →The 24-cell in the proper sequence of 4-polytopes: sharpest and roundest |

(No difference)

|

Latest revision as of 21:41, 12 March 2025

The unique 24-point 24-cell polytope

The 24-cell does not have a regular analogue in three dimensions or any other number of dimensions.Template:Sfn It is the only one of the six convex regular 4-polytopes which is not the analogue of one of the five Platonic solids. However, it can be seen as the analogue of a pair of irregular solids: the cuboctahedron and its dual the rhombic dodecahedron.Template:Sfn

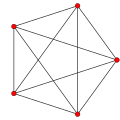

The 24-cell and the 8-cell (tesseract) are the only convex regular 4-polytopes in which the edge length equals the radius. The long radius (center to vertex) of each is equal to its edge length; thus its long diameter (vertex to opposite vertex) is 2 edge lengths. Only a few uniform polytopes have this property, including these two four-dimensional polytopes, the three-dimensional cuboctahedron, and the two-dimensional hexagon. The cuboctahedron is the equatorial cross section of the 24-cell, and the hexagon is the equatorial cross section of the cuboctahedron. These radially equilateral polytopes are those which can be constructed, with their long radii, from equilateral triangles which meet at the center of the polytope, each contributing two radii and an edge.

The 24-cell in the proper sequence of 4-polytopes

The 24-cell incorporates the geometries of every convex regular polytope in the first four dimensions, except the 5-cell (4-simplex), those with a 5 in their Schlӓfli symbol,Template:Efn and the regular polygons with 7 or more sides. In other words, the 24-cell contains all of the regular polytopes made of triangles and squares that exist in four dimensions except the regular 5-cell, but none of the pentagonal polytopes. It is especially useful to explore the 24-cell, because one can see the geometric relationships among all of these regular polytopes in a single 24-cell or its honeycomb.

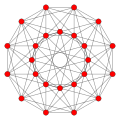

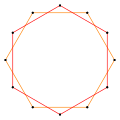

The 24-cell is the fourth in the sequence of six convex regular 4-polytopes in order of size and complexity. These can be ordered by size as a measure of 4-dimensional content (hypervolume) for the same radius. This is their proper order of enumeration: the order in which they nest inside each other as compounds.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn Each greater polytope in the sequence is rounder than its predecessor, enclosing more contentTemplate:Sfn within the same radius. The 5-cell (4-simplex) is the limit smallest (and sharpest) case, and the 120-cell is the largest (and roundest). Complexity (as measured by comparing configuration matrices or simply the number of vertices) follows the same ordering. This provides an alternative numerical naming scheme for regular polytopes in which the 24-cell is the 24-point 4-polytope: fourth in the ascending sequence that runs from 5-point (5-cell) 4-polytope to 600-point (120-cell) 4-polytope.

The 24-cell can be deconstructed into 3 overlapping instances of its predecessor the 8-cell (tesseract), as the 8-cell can be deconstructed into 2 instances of its predecessor the 16-cell.Template:Sfn The reverse procedure to construct each of these from an instance of its predecessor preserves the radius of the predecessor, but generally produces a successor with a smaller edge length. The edge length will always be different unless predecessor and successor are both radially equilateral, i.e. their edge length is the same as their radius (so both are preserved). Since radially equilateral polytopes are rare, it seems that the only such construction (in any dimension) is from the 8-cell to the 24-cell, making the 24-cell the unique regular polytope (in any dimension) which has the same edge length as its predecessor of the same radius.

Coordinates

The 24-cell has two natural systems of Cartesian coordinates, which reveal distinct structure.

Great squares

The 24-cell is the convex hull of its vertices which can be described as the 24 coordinate permutations of:

Those coordinatesTemplate:Sfn can be constructed as Template:Coxeter–Dynkin diagram, rectifying the 16-cell Template:Coxeter–Dynkin diagram with 8 vertices permutations of (±2,0,0,0). The vertex figure of a 16-cell is the octahedron; thus, cutting the vertices of the 16-cell at the midpoint of its incident edges produces 8 octahedral cells. This processTemplate:Sfn also rectifies the tetrahedral cells of the 16-cell which become 16 octahedra, giving the 24-cell 24 octahedral cells.

In this frame of reference the 24-cell has edges of length Template:Sqrt and is inscribed in a 3-sphere of radius Template:Sqrt. Remarkably, the edge length equals the circumradius, as in the hexagon, or the cuboctahedron.

The 24 vertices form 18 great squaresTemplate:Efn (3 sets of 6 orthogonalTemplate:Efn central squares), 3 of which intersect at each vertex. By viewing just one square at each vertex, the 24-cell can be seen as the vertices of 3 pairs of completely orthogonalTemplate:Efn great squares which intersectTemplate:Efn at no vertices.Template:Efn

Great hexagons

The 24-cell is self-dual, having the same number of vertices (24) as cells and the same number of edges (96) as faces.

If the dual of the above 24-cell of edge length Template:Sqrt is taken by reciprocating it about its inscribed sphere, another 24-cell is found which has edge length and circumradius 1, and its coordinates reveal more structure. In this frame of reference the 24-cell lies vertex-up, and its vertices can be given as follows:

8 vertices obtained by permuting the integer coordinates:

and 16 vertices with half-integer coordinates of the form:

all 24 of which lie at distance 1 from the origin.

Viewed as quaternions,Template:Efn these are the unit Hurwitz quaternions. These 24 quaternions represent (in antipodal pairs) the 12 rotations of a regular tetrahedron.Template:Sfn

The 24-cell has unit radius and unit edge length in this coordinate system. We refer to the system as unit radius coordinates to distinguish it from others, such as the Template:Sqrt radius coordinates used to reveal the great squares above.Template:Efn

The 24 vertices and 96 edges form 16 non-orthogonal great hexagons,Template:Efn four of which intersectTemplate:Efn at each vertex.Template:Efn By viewing just one hexagon at each vertex, the 24-cell can be seen as the 24 vertices of 4 non-intersecting hexagonal great circles which are Clifford parallel to each other.Template:Efn

The 12 axes and 16 hexagons of the 24-cell constitute a Reye configuration, which in the language of configurations is written as 124163 to indicate that each axis belongs to 4 hexagons, and each hexagon contains 3 axes.Template:Sfn

Great triangles

The 24 vertices form 32 equilateral great triangles, of edge length Template:Radic in the unit-radius 24-cell,Template:Efn inscribed in the 16 great hexagons.Template:Efn

Each great triangle is a ring linking three completely disjointTemplate:Efn great squares. The 18 great squares of the 24-cell occur as three sets of 6 orthogonal great squares,Template:Efn each forming a 16-cell.Template:Efn The three 16-cells are completely disjoint (and Clifford parallel): each has its own 8 vertices (on 4 orthogonal axes) and its own 24 edges (of length Template:Radic). The 18 square great circles are crossed by 16 hexagonal great circles; each hexagon has one axis (2 vertices) in each 16-cell.Template:Efn The two great triangles inscribed in each great hexagon (occupying its alternate vertices, and with edges that are its Template:Radic chords) have one vertex in each 16-cell. Thus each great triangle is a ring linking the three completely disjoint 16-cells. There are four different ways (four different fibrations of the 24-cell) in which the 8 vertices of the 16-cells correspond by being triangles of vertices Template:Radic apart: there are 32 distinct linking triangles. Each pair of 16-cells forms an 8-cell (tesseract).Template:Efn Each great triangle has one Template:Radic edge in each tesseract, so it is also a ring linking the three tesseracts.

Hypercubic chords

The 24 vertices of the 24-cell are distributedTemplate:Sfn at four different chord lengths from each other: Template:Sqrt, Template:Sqrt, Template:Sqrt and Template:Sqrt. The Template:Sqrt chords (the 24-cell edges) are the edges of central hexagons, and the Template:Sqrt chords are the diagonals of central hexagons. The Template:Sqrt chords are the edges of central squares, and the Template:Sqrt chords are the diagonals of central squares.

Each vertex is joined to 8 othersTemplate:Efn by an edge of length 1, spanning 60° = Template:Sfrac of arc. Next nearest are 6 verticesTemplate:Efn located 90° = Template:Sfrac away, along an interior chord of length Template:Sqrt. Another 8 vertices lie 120° = Template:Sfrac away, along an interior chord of length Template:Sqrt.Template:Efn The opposite vertex is 180° = Template:Pi away along a diameter of length 2. Finally, as the 24-cell is radially equilateral, its center is 1 edge length away from all vertices.

To visualize how the interior polytopes of the 24-cell fit together (as described below), keep in mind that the four chord lengths (Template:Sqrt, Template:Sqrt, Template:Sqrt, Template:Sqrt) are the long diameters of the hypercubes of dimensions 1 through 4: the long diameter of the square is Template:Sqrt; the long diameter of the cube is Template:Sqrt; and the long diameter of the tesseract is Template:Sqrt.Template:Efn Moreover, the long diameter of the octahedron is Template:Sqrt like the square; and the long diameter of the 24-cell itself is Template:Sqrt like the tesseract.

Geodesics

The vertex chords of the 24-cell are arranged in geodesic great circle polygons.Template:Efn The geodesic distance between two 24-cell vertices along a path of Template:Sqrt edges is always 1, 2, or 3, and it is 3 only for opposite vertices.Template:Efn

The Template:Sqrt edges occur in 16 hexagonal great circles (in planes inclined at 60 degrees to each other), 4 of which crossTemplate:Efn at each vertex.Template:Efn The 96 distinct Template:Sqrt edges divide the surface into 96 triangular faces and 24 octahedral cells: a 24-cell. The 16 hexagonal great circles can be divided into 4 sets of 4 non-intersecting Clifford parallel geodesics, such that only one hexagonal great circle in each set passes through each vertex, and the 4 hexagons in each set reach all 24 vertices.Template:Efn

The Template:Sqrt chords occur in 18 square great circles (3 sets of 6 orthogonal planesTemplate:Efn), 3 of which cross at each vertex.Template:Efn The 72 distinct Template:Sqrt chords do not run in the same planes as the hexagonal great circles; they do not follow the 24-cell's edges, they pass through its octagonal cell centers.Template:Efn The 72 Template:Sqrt chords are the 3 orthogonal axes of the 24 octahedral cells, joining vertices which are 2 Template:Radic edges apart. The 18 square great circles can be divided into 3 sets of 6 non-intersecting Clifford parallel geodesics,Template:Efn such that only one square great circle in each set passes through each vertex, and the 6 squares in each set reach all 24 vertices.Template:Efn

The Template:Sqrt chords occur in 32 triangular great circles in 16 planes, 4 of which cross at each vertex.Template:Efn The 96 distinct Template:Sqrt chordsTemplate:Efn run vertex-to-every-other-vertex in the same planes as the hexagonal great circles.Template:Efn They are the 3 edges of the 32 great triangles inscribed in the 16 great hexagons, joining vertices which are 2 Template:Sqrt edges apart on a great circle.Template:Efn

The Template:Sqrt chords occur as 12 vertex-to-vertex diameters (3 sets of 4 orthogonal axes), the 24 radii around the 25th central vertex.

The sum of the squared lengthsTemplate:Efn of all these distinct chords of the 24-cell is 576 = 242.Template:Efn These are all the central polygons through vertices, but in 4-space there are geodesics on the 3-sphere which do not lie in central planes at all. There are geodesic shortest paths between two 24-cell vertices that are helical rather than simply circular; they correspond to diagonal isoclinic rotations rather than simple rotations.Template:Efn

The Template:Sqrt edges occur in 48 parallel pairs, Template:Sqrt apart. The Template:Sqrt chords occur in 36 parallel pairs, Template:Sqrt apart. The Template:Sqrt chords occur in 48 parallel pairs, Template:Sqrt apart.Template:Efn

The central planes of the 24-cell can be divided into 4 orthogonal central hyperplanes (3-spaces) each forming a cuboctahedron. The great hexagons are 60 degrees apart; the great squares are 90 degrees or 60 degrees apart; a great square and a great hexagon are 90 degrees and 60 degrees apart.Template:Efn Each set of similar central polygons (squares or hexagons) can be divided into 4 sets of non-intersecting Clifford parallel polygons (of 6 squares or 4 hexagons).Template:Efn Each set of Clifford parallel great circles is a parallel fiber bundle which visits all 24 vertices just once.

Each great circle intersectsTemplate:Efn with the other great circles to which it is not Clifford parallel at one Template:Sqrt diameter of the 24-cell.Template:Efn Great circles which are completely orthogonal or otherwise Clifford parallelTemplate:Efn do not intersect at all: they pass through disjoint sets of vertices.Template:Efn

Constructions

Triangles and squares come together uniquely in the 24-cell to generate, as interior features,Template:Efn all of the triangle-faced and square-faced regular convex polytopes in the first four dimensions (with caveats for the 5-cell and the 600-cell).Template:Efn Consequently, there are numerous ways to construct or deconstruct the 24-cell.

Reciprocal constructions from 8-cell and 16-cell

The 8 integer vertices (±1, 0, 0, 0) are the vertices of a regular 16-cell, and the 16 half-integer vertices (±Template:Sfrac, ±Template:Sfrac, ±Template:Sfrac, ±Template:Sfrac) are the vertices of its dual, the 8-cell (tesseract).Template:Sfn The tesseract gives Gosset's constructionTemplate:Sfn of the 24-cell, equivalent to cutting a tesseract into 8 cubic pyramids, and then attaching them to the facets of a second tesseract. The analogous construction in 3-space gives the rhombic dodecahedron which, however, is not regular.Template:Efn The 16-cell gives the reciprocal construction of the 24-cell, Cesaro's construction,Template:Sfn equivalent to rectifying a 16-cell (truncating its corners at the mid-edges, as described above). The analogous construction in 3-space gives the cuboctahedron (dual of the rhombic dodecahedron) which, however, is not regular. The tesseract and the 16-cell are the only regular 4-polytopes in the 24-cell.Template:Sfn

We can further divide the 16 half-integer vertices into two groups: those whose coordinates contain an even number of minus (−) signs and those with an odd number. Each of these groups of 8 vertices also define a regular 16-cell. This shows that the vertices of the 24-cell can be grouped into three disjoint sets of eight with each set defining a regular 16-cell, and with the complement defining the dual tesseract.Template:Sfn This also shows that the symmetries of the 16-cell form a subgroup of index 3 of the symmetry group of the 24-cell.Template:Efn

Diminishings

We can facet the 24-cell by cuttingTemplate:Efn through interior cells bounded by vertex chords to remove vertices, exposing the facets of interior 4-polytopes inscribed in the 24-cell. One can cut a 24-cell through any planar hexagon of 6 vertices, any planar rectangle of 4 vertices, or any triangle of 3 vertices. The great circle central planes (above) are only some of those planes. Here we shall expose some of the others: the face planesTemplate:Efn of interior polytopes.Template:Efn

8-cell

Starting with a complete 24-cell, remove 8 orthogonal vertices (4 opposite pairs on 4 perpendicular axes), and the 8 edges which radiate from each, by cutting through 8 cubic cells bounded by Template:Sqrt edges to remove 8 cubic pyramids whose apexes are the vertices to be removed. This removes 4 edges from each hexagonal great circle (retaining just one opposite pair of edges), so no continuous hexagonal great circles remain. Now 3 perpendicular edges meet and form the corner of a cube at each of the 16 remaining vertices,Template:Efn and the 32 remaining edges divide the surface into 24 square faces and 8 cubic cells: a tesseract. There are three ways you can do this (choose a set of 8 orthogonal vertices out of 24), so there are three such tesseracts inscribed in the 24-cell.Template:Efn They overlap with each other, but most of their element sets are disjoint: they share some vertex count, but no edge length, face area, or cell volume.Template:Efn They do share 4-content, their common core.Template:Efn

16-cell

Starting with a complete 24-cell, remove the 16 vertices of a tesseract (retaining the 8 vertices you removed above), by cutting through 16 tetrahedral cells bounded by Template:Sqrt chords to remove 16 tetrahedral pyramids whose apexes are the vertices to be removed. This removes 12 great squares (retaining just one orthogonal set) and all the Template:Sqrt edges, exposing Template:Sqrt chords as the new edges. Now the remaining 6 great squares cross perpendicularly, 3 at each of 8 remaining vertices,Template:Efn and their 24 edges divide the surface into 32 triangular faces and 16 tetrahedral cells: a 16-cell. There are three ways you can do this (remove 1 of 3 sets of tesseract vertices), so there are three such 16-cells inscribed in the 24-cell.Template:Efn They overlap with each other, but all of their element sets are disjoint:Template:Efn they do not share any vertex count, edge length,Template:Efn or face area, but they do share cell volume. They also share 4-content, their common core.Template:Efn

Tetrahedral constructions

The 24-cell can be constructed radially from 96 equilateral triangles of edge length Template:Sqrt which meet at the center of the polytope, each contributing two radii and an edge. They form 96 Template:Sqrt tetrahedra (each contributing one 24-cell face), all sharing the 25th central apex vertex. These form 24 octahedral pyramids (half-16-cells) with their apexes at the center.

The 24-cell can be constructed from 96 equilateral triangles of edge length Template:Sqrt, where the three vertices of each triangle are located 90° = Template:Sfrac away from each other on the 3-sphere. They form 48 Template:Sqrt-edge tetrahedra (the cells of the three 16-cells), centered at the 24 mid-edge-radii of the 24-cell.Template:Efn

The 24-cell can be constructed directly from its characteristic simplex Template:Coxeter–Dynkin diagram, the irregular 5-cell which is the fundamental region of its symmetry group F4, by reflection of that 4-orthoscheme in its own cells (which are 3-orthoschemes).Template:Efn

Cubic constructions

The 24-cell is not only the 24-octahedral-cell, it is also the 24-cubical-cell, although the cubes are cells of the three 8-cells, not cells of the 24-cell, in which they are not volumetrically disjoint.

The 24-cell can be constructed from 24 cubes of its own edge length (three 8-cells).Template:Efn Each of the cubes is shared by 2 8-cells, each of the cubes' square faces is shared by 4 cubes (in 2 8-cells), each of the 96 edges is shared by 8 square faces (in 4 cubes in 2 8-cells), and each of the 96 vertices is shared by 16 edges (in 8 square faces in 4 cubes in 2 8-cells).

Relationships among interior polytopes

The 24-cell, three tesseracts, and three 16-cells are deeply entwined around their common center, and intersect in a common core.Template:Efn The tesseracts and the 16-cells are rotated 60° isoclinicallyTemplate:Efn with respect to each other. This means that the corresponding vertices of two tesseracts or two 16-cells are Template:Radic (120°) apart.Template:Efn

The tesseracts are inscribed in the 24-cellTemplate:Efn such that their vertices and edges are exterior elements of the 24-cell, but their square faces and cubical cells lie inside the 24-cell (they are not elements of the 24-cell). The 16-cells are inscribed in the 24-cellTemplate:Efn such that only their vertices are exterior elements of the 24-cell: their edges, triangular faces, and tetrahedral cells lie inside the 24-cell. The interiorTemplate:Efn 16-cell edges have length Template:Sqrt.

The 16-cells are also inscribed in the tesseracts: their Template:Sqrt edges are the face diagonals of the tesseract, and their 8 vertices occupy every other vertex of the tesseract. Each tesseract has two 16-cells inscribed in it (occupying the opposite vertices and face diagonals), so each 16-cell is inscribed in two of the three 8-cells.Template:SfnTemplate:Efn This is reminiscent of the way, in 3 dimensions, two opposing regular tetrahedra can be inscribed in a cube, as discovered by Kepler.Template:Sfn In fact it is the exact dimensional analogy (the demihypercubes), and the 48 tetrahedral cells are inscribed in the 24 cubical cells in just that way.Template:SfnTemplate:Efn

The 24-cell encloses the three tesseracts within its envelope of octahedral facets, leaving 4-dimensional space in some places between its envelope and each tesseract's envelope of cubes. Each tesseract encloses two of the three 16-cells, leaving 4-dimensional space in some places between its envelope and each 16-cell's envelope of tetrahedra. Thus there are measurableTemplate:Sfn 4-dimensional intersticesTemplate:Efn between the 24-cell, 8-cell and 16-cell envelopes. The shapes filling these gaps are 4-pyramids, alluded to above.Template:Efn

Boundary cells

Despite the 4-dimensional interstices between 24-cell, 8-cell and 16-cell envelopes, their 3-dimensional volumes overlap. The different envelopes are separated in some places, and in contact in other places (where no 4-pyramid lies between them). Where they are in contact, they merge and share cell volume: they are the same 3-membrane in those places, not two separate but adjacent 3-dimensional layers.Template:Efn Because there are a total of 7 envelopes, there are places where several envelopes come together and merge volume, and also places where envelopes interpenetrate (cross from inside to outside each other).

Some interior features lie within the 3-space of the (outer) boundary envelope of the 24-cell itself: each octahedral cell is bisected by three perpendicular squares (one from each of the tesseracts), and the diagonals of those squares (which cross each other perpendicularly at the center of the octahedron) are 16-cell edges (one from each 16-cell). Each square bisects an octahedron into two square pyramids, and also bonds two adjacent cubic cells of a tesseract together as their common face.Template:Efn

As we saw above, 16-cell Template:Sqrt tetrahedral cells are inscribed in tesseract Template:Sqrt cubic cells, sharing the same volume. 24-cell Template:Sqrt octahedral cells overlap their volume with Template:Sqrt cubic cells: they are bisected by a square face into two square pyramids,Template:Sfn the apexes of which also lie at a vertex of a cube.Template:Efn The octahedra share volume not only with the cubes, but with the tetrahedra inscribed in them; thus the 24-cell, tesseracts, and 16-cells all share some boundary volume.Template:Efn

Radially equilateral honeycomb

The dual tessellation of the 24-cell honeycomb {3,4,3,3} is the 16-cell honeycomb {3,3,4,3}. The third regular tessellation of four dimensional space is the tesseractic honeycomb {4,3,3,4}, whose vertices can be described by 4-integer Cartesian coordinates.Template:Efn The congruent relationships among these three tessellations can be helpful in visualizing the 24-cell, in particular the radial equilateral symmetry which it shares with the tesseract.

A honeycomb of unit edge length 24-cells may be overlaid on a honeycomb of unit edge length tesseracts such that every vertex of a tesseract (every 4-integer coordinate) is also the vertex of a 24-cell (and tesseract edges are also 24-cell edges), and every center of a 24-cell is also the center of a tesseract.Template:Sfn The 24-cells are twice as large as the tesseracts by 4-dimensional content (hypervolume), so overall there are two tesseracts for every 24-cell, only half of which are inscribed in a 24-cell. If those tesseracts are colored black, and their adjacent tesseracts (with which they share a cubical facet) are colored red, a 4-dimensional checkerboard results.Template:Sfn Of the 24 center-to-vertex radiiTemplate:Efn of each 24-cell, 16 are also the radii of a black tesseract inscribed in the 24-cell. The other 8 radii extend outside the black tesseract (through the centers of its cubical facets) to the centers of the 8 adjacent red tesseracts. Thus the 24-cell honeycomb and the tesseractic honeycomb coincide in a special way: 8 of the 24 vertices of each 24-cell do not occur at a vertex of a tesseract (they occur at the center of a tesseract instead). Each black tesseract is cut from a 24-cell by truncating it at these 8 vertices, slicing off 8 cubic pyramids (as in reversing Gosset's construction,Template:Sfn but instead of being removed the pyramids are simply colored red and left in place). Eight 24-cells meet at the center of each red tesseract: each one meets its opposite at that shared vertex, and the six others at a shared octahedral cell.

The red tesseracts are filled cells (they contain a central vertex and radii); the black tesseracts are empty cells. The vertex set of this union of two honeycombs includes the vertices of all the 24-cells and tesseracts, plus the centers of the red tesseracts. Adding the 24-cell centers (which are also the black tesseract centers) to this honeycomb yields a 16-cell honeycomb, the vertex set of which includes all the vertices and centers of all the 24-cells and tesseracts. The formerly empty centers of adjacent 24-cells become the opposite vertices of a unit edge length 16-cell. 24 half-16-cells (octahedral pyramids) meet at each formerly empty center to fill each 24-cell, and their octahedral bases are the 6-vertex octahedral facets of the 24-cell (shared with an adjacent 24-cell).Template:Efn

Notice the complete absence of pentagons anywhere in this union of three honeycombs. Like the 24-cell, 4-dimensional Euclidean space itself is entirely filled by a complex of all the polytopes that can be built out of regular triangles and squares (except the 5-cell), but that complex does not require (or permit) any of the pentagonal polytopes.Template:Efn

Rotations

The regular convex 4-polytopes are an expression of their underlying symmetry which is known as SO(4),Template:Sfn the group of rotationsTemplate:Sfn about a fixed point in 4-dimensional Euclidean space.Template:Efn

The 3 Cartesian bases of the 24-cell

There are three distinct orientations of the tesseractic honeycomb which could be made to coincide with the 24-cell honeycomb, depending on which of the 24-cell's three disjoint sets of 8 orthogonal vertices (which set of 4 perpendicular axes, or equivalently, which inscribed basis 16-cell)Template:Efn was chosen to align it, just as three tesseracts can be inscribed in the 24-cell, rotated with respect to each other.Template:Efn The distance from one of these orientations to another is an isoclinic rotation through 60 degrees (a double rotation of 60 degrees in each pair of orthogonal invariant planes, around a single fixed point).Template:Efn This rotation can be seen most clearly in the hexagonal central planes, where every hexagon rotates to change which of its three diameters is aligned with a coordinate system axis.Template:Efn

Planes of rotation

Rotations in 4-dimensional Euclidean space can be seen as the composition of two 2-dimensional rotations in completely orthogonal planes.Template:Sfn Thus the general rotation in 4-space is a double rotation.Template:Sfn There are two important special cases, called a simple rotation and an isoclinic rotation.Template:Efn

Simple rotations

In 3 dimensions a spinning polyhedron has a single invariant central plane of rotation. The plane is an invariant set because each point in the plane moves in a circle but stays within the plane. Only one of a polyhedron's central planes can be invariant during a particular rotation; the choice of invariant central plane, and the angular distance and direction it is rotated, completely specifies the rotation. Points outside the invariant plane also move in circles (unless they are on the fixed axis of rotation perpendicular to the invariant plane), but the circles do not lie within a central plane.

When a 4-polytope is rotating with only one invariant central plane, the same kind of simple rotation is happening that occurs in 3 dimensions. One difference is that instead of a fixed axis of rotation, there is an entire fixed central plane in which the points do not move. The fixed plane is the one central plane that is completely orthogonalTemplate:Efn to the invariant plane of rotation. In the 24-cell, there is a simple rotation which will take any vertex directly to any other vertex, also moving most of the other vertices but leaving at least 2 and at most 6 other vertices fixed (the vertices that the fixed central plane intersects). The vertex moves along a great circle in the invariant plane of rotation between adjacent vertices of a great hexagon, a great square or a great digon, and the completely orthogonal fixed plane is a digon, a square or a hexagon, respectively. Template:Efn

Double rotations

The points in the completely orthogonal central plane are not constrained to be fixed. It is also possible for them to be rotating in circles, as a second invariant plane, at a rate independent of the first invariant plane's rotation: a double rotation in two perpendicular non-intersecting planesTemplate:Efn of rotation at once.Template:Efn In a double rotation there is no fixed plane or axis: every point moves except the center point. The angular distance rotated may be different in the two completely orthogonal central planes, but they are always both invariant: their circularly moving points remain within the plane as the whole plane tilts sideways in the completely orthogonal rotation. A rotation in 4-space always has (at least) two completely orthogonal invariant planes of rotation, although in a simple rotation the angle of rotation in one of them is 0.

Double rotations come in two chiral forms: left and right rotations.Template:Efn In a double rotation each vertex moves in a spiral along two orthogonal great circles at once.Template:Efn Either the path is right-hand threaded (like most screws and bolts), moving along the circles in the "same" directions, or it is left-hand threaded (like a reverse-threaded bolt), moving along the circles in what we conventionally say are "opposite" directions (according to the right hand rule by which we conventionally say which way is "up" on each of the 4 coordinate axes).Template:Sfn

In double rotations of the 24-cell that take vertices to vertices, one invariant plane of rotation contains either a great hexagon, a great square, or only an axis (two vertices, a great digon). The completely orthogonal invariant plane of rotation will necessarily contain a great digon, a great square, or a great hexagon, respectively. The selection of an invariant plane of rotation, a rotational direction and angle through which to rotate it, and a rotational direction and angle through which to rotate its completely orthogonal plane, completely determines the nature of the rotational displacement. In the 24-cell there are several noteworthy kinds of double rotation permitted by these parameters.Template:Sfn

Isoclinic rotations

When the angles of rotation in the two completely orthogonal invariant planes are exactly the same, a remarkably symmetric transformation occurs:Template:Sfn all the great circle planes Clifford parallelTemplate:Efn to the pair of invariant planes become pairs of invariant planes of rotation themselves, through that same angle, and the 4-polytope rotates isoclinically in many directions at once.Template:Sfn Each vertex moves an equal distance in four orthogonal directions at the same time.Template:Efn In the 24-cell any isoclinic rotation through 60 degrees in a hexagonal plane takes each vertex to a vertex two edge lengths away, rotates all 16 hexagons by 60 degrees, and takes every great circle polygon (square,Template:Efn hexagon or triangle) to a Clifford parallel great circle polygon of the same kind 120 degrees away. An isoclinic rotation is also called a Clifford displacement, after its discoverer.Template:Efn

The 24-cell in the double rotation animation appears to turn itself inside out.Template:Efn It appears to, because it actually does, reversing the chirality of the whole 4-polytope just the way your bathroom mirror reverses the chirality of your image by a 180 degree reflection. Each 360 degree isoclinic rotation is as if the 24-cell surface had been stripped off like a glove and turned inside out, making a right-hand glove into a left-hand glove (or vice versa).Template:Sfn

In a simple rotation of the 24-cell in a hexagonal plane, each vertex in the plane rotates first along an edge to an adjacent vertex 60 degrees away. But in an isoclinic rotation in two completely orthogonal planes one of which is a great hexagon,Template:Efn each vertex rotates first to a vertex two edge lengths away (Template:Radic and 120° distant). The double 60-degree rotation's helical geodesics pass through every other vertex, missing the vertices in between.Template:Efn Each Template:Radic chord of the helical geodesicTemplate:Efn crosses between two Clifford parallel hexagon central planes, and lies in another hexagon central plane that intersects them both.Template:Efn The Template:Radic chords meet at a 60° angle, but since they lie in different planes they form a helix not a triangle. Three Template:Radic chords and 360° of rotation takes the vertex to an adjacent vertex, not back to itself. The helix of Template:Radic chords closes into a loop only after six Template:Radic chords: a 720° rotation twice around the 24-cellTemplate:Efn on a skew hexagram with Template:Radic edges.Template:Efn Even though all 24 vertices and all the hexagons rotate at once, a 360 degree isoclinic rotation moves each vertex only halfway around its circuit. After 360 degrees each helix has departed from 3 vertices and reached a fourth vertex adjacent to the original vertex, but has not arrived back exactly at the vertex it departed from. Each central plane (every hexagon or square in the 24-cell) has rotated 360 degrees and been tilted sideways all the way around 360 degrees back to its original position (like a coin flipping twice), but the 24-cell's orientation in the 4-space in which it is embedded is now different.Template:Sfn Because the 24-cell is now inside-out, if the isoclinic rotation is continued in the same direction through another 360 degrees, the 24 moving vertices will pass through the other half of the vertices that were missed on the first revolution (the 12 antipodal vertices of the 12 that were hit the first time around), and each isoclinic geodesic will arrive back at the vertex it departed from, forming a closed six-chord helical loop. It takes a 720 degree isoclinic rotation for each hexagram2 geodesic to complete a circuit through every second vertex of its six vertices by winding around the 24-cell twice, returning the 24-cell to its original chiral orientation.Template:Efn

The hexagonal winding path that each vertex takes as it loops twice around the 24-cell forms a double helix bent into a Möbius ring, so that the two strands of the double helix form a continuous single strand in a closed loop.Template:Efn In the first revolution the vertex traverses one 3-chord strand of the double helix; in the second revolution it traverses the second 3-chord strand, moving in the same rotational direction with the same handedness (bending either left or right) throughout. Although this isoclinic Möbius ring is a circular spiral through all 4 dimensions, not a 2-dimensional circle, like a great circle it is a geodesic because it is the shortest path from vertex to vertex.Template:Efn

Clifford parallel polytopes

Two planes are also called isoclinic if an isoclinic rotation will bring them together.Template:Efn The isoclinic planes are precisely those central planes with Clifford parallel geodesic great circles.Template:Sfn Clifford parallel great circles do not intersect,Template:Efn so isoclinic great circle polygons have disjoint vertices. In the 24-cell every hexagonal central plane is isoclinic to three others, and every square central plane is isoclinic to five others. We can pick out 4 mutually isoclinic (Clifford parallel) great hexagons (four different ways) covering all 24 vertices of the 24-cell just once (a hexagonal fibration).Template:Efn We can pick out 6 mutually isoclinic (Clifford parallel) great squaresTemplate:Efn (three different ways) covering all 24 vertices of the 24-cell just once (a square fibration).Template:Efn Every isoclinic rotation taking vertices to vertices corresponds to a discrete fibration.Template:Efn

Two dimensional great circle polygons are not the only polytopes in the 24-cell which are parallel in the Clifford sense.Template:Sfn Congruent polytopes of 2, 3 or 4 dimensions can be said to be Clifford parallel in 4 dimensions if their corresponding vertices are all the same distance apart. The three 16-cells inscribed in the 24-cell are Clifford parallels. Clifford parallel polytopes are completely disjoint polytopes.Template:Efn A 60 degree isoclinic rotation in hexagonal planes takes each 16-cell to a disjoint 16-cell. Like all double rotations, isoclinic rotations come in two chiral forms: there is a disjoint 16-cell to the left of each 16-cell, and another to its right.Template:Efn

All Clifford parallel 4-polytopes are related by an isoclinic rotation,Template:Efn but not all isoclinic polytopes are Clifford parallels (completely disjoint).Template:Efn The three 8-cells in the 24-cell are isoclinic but not Clifford parallel. Like the 16-cells, they are rotated 60 degrees isoclinically with respect to each other, but their vertices are not all disjoint (and therefore not all equidistant). Each vertex occurs in two of the three 8-cells (as each 16-cell occurs in two of the three 8-cells).Template:Efn

Isoclinic rotations relate the convex regular 4-polytopes to each other. An isoclinic rotation of a single 16-cell will generateTemplate:Efn a 24-cell. A simple rotation of a single 16-cell will not, because its vertices will not reach either of the other two 16-cells' vertices in the course of the rotation. An isoclinic rotation of the 24-cell will generate the 600-cell, and an isoclinic rotation of the 600-cell will generate the 120-cell. (Or they can all be generated directly by an isoclinic rotation of the 16-cell, generating isoclinic copies of itself.) The different convex regular 4-polytopes nest inside each other, and multiple instances of the same 4-polytope hide next to each other in the Clifford parallel spaces that comprise the 3-sphere.Template:Sfn For an object of more than one dimension, the only way to reach these parallel subspaces directly is by isoclinic rotation. Like a key operating a four-dimensional lock, an object must twist in two completely perpendicular tumbler cylinders at once in order to move the short distance between Clifford parallel subspaces.

Rings

In the 24-cell there are sets of rings of six different kinds, described separately in detail in other sections of this article. This section describes how the different kinds of rings are intertwined.

The 24-cell contains four kinds of geodesic fibers (polygonal rings running through vertices): great circle squares and their isoclinic helix octagrams,Template:Efn and great circle hexagons and their isoclinic helix hexagrams.Template:Efn It also contains two kinds of cell rings (chains of octahedra bent into a ring in the fourth dimension): four octahedra connected vertex-to-vertex and bent into a square, and six octahedra connected face-to-face and bent into a hexagon.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn

4-cell rings

Four unit-edge-length octahedra can be connected vertex-to-vertex along a common axis of length 4Template:Radic. The axis can then be bent into a square of edge length Template:Radic. Although it is possible to do this in a space of only three dimensions, that is not how it occurs in the 24-cell. Although the Template:Radic axes of the four octahedra occupy the same plane, forming one of the 18 Template:Radic great squares of the 24-cell, each octahedron occupies a different 3-dimensional hyperplane,Template:Efn and all four dimensions are utilized. The 24-cell can be partitioned into 6 such 4-cell rings (three different ways), mutually interlinked like adjacent links in a chain (but these links all have a common center). An isoclinic rotation in the great square plane by a multiple of 90° takes each octahedron in the ring to an octahedron in the ring.

6-cell rings

Six regular octahedra can be connected face-to-face along a common axis that passes through their centers of volume, forming a stack or column with only triangular faces. In a space of four dimensions, the axis can then be bent 60° in the fourth dimension at each of the six octahedron centers, in a plane orthogonal to all three orthogonal central planes of each octahedron, such that the top and bottom triangular faces of the column become coincident. The column becomes a ring around a hexagonal axis. The 24-cell can be partitioned into 4 such rings (four different ways), mutually interlinked. Because the hexagonal axis joins cell centers (not vertices), it is not a great hexagon of the 24-cell.Template:Efn However, six great hexagons can be found in the ring of six octahedra, running along the edges of the octahedra. In the column of six octahedra (before it is bent into a ring) there are six spiral paths along edges running up the column: three parallel helices spiraling clockwise, and three parallel helices spiraling counterclockwise. Each clockwise helix intersects each counterclockwise helix at two vertices three edge lengths apart. Bending the column into a ring changes these helices into great circle hexagons.Template:Efn The ring has two sets of three great hexagons, each on three Clifford parallel great circles.Template:Efn The great hexagons in each parallel set of three do not intersect, but each intersects the other three great hexagons (to which it is not Clifford parallel) at two antipodal vertices.

A simple rotation in any of the great hexagon planes by a multiple of 60° rotates only that hexagon invariantly, taking each vertex in that hexagon to a vertex in the same hexagon. An isoclinic rotation by 60° in any of the six great hexagon planes rotates all three Clifford parallel great hexagons invariantly, and takes each octahedron in the ring to a non-adjacent octahedron in the ring.Template:Efn

Each isoclinically displaced octahedron is also rotated itself. After a 360° isoclinic rotation each octahedron is back in the same position, but in a different orientation. In a 720° isoclinic rotation, its vertices are returned to their original orientation.

Four Clifford parallel great hexagons comprise a discrete fiber bundle covering all 24 vertices in a Hopf fibration. The 24-cell has four such discrete hexagonal fibrations . Each great hexagon belongs to just one fibration, and the four fibrations are defined by disjoint sets of four great hexagons each.Template:Sfn Each fibration is the domain (container) of a unique left-right pair of isoclinic rotations (left and right Hopf fiber bundles).Template:Efn

Four cell-disjoint 6-cell rings also comprise each discrete fibration defined by four Clifford parallel great hexagons. Each 6-cell ring contains only 18 of the 24 vertices, and only 6 of the 16 great hexagons, which we see illustrated above running along the cell ring's edges: 3 spiraling clockwise and 3 counterclockwise. Those 6 hexagons running along the cell ring's edges are not among the set of four parallel hexagons which define the fibration. For example, one of the four 6-cell rings in fibration contains 3 parallel hexagons running clockwise along the cell ring's edges from fibration , and 3 parallel hexagons running counterclockwise along the cell ring's edges from fibration , but that cell ring contains no great hexagons from fibration or fibration .

The 24-cell contains 16 great hexagons, divided into four disjoint sets of four hexagons, each disjoint set uniquely defining a fibration. Each fibration is also a distinct set of four cell-disjoint 6-cell rings. The 24-cell has exactly 16 distinct 6-cell rings. Each 6-cell ring belongs to just one of the four fibrations.Template:Efn

Helical hexagrams and their isoclines

Another kind of geodesic fiber, the helical hexagram isoclines, can be found within a 6-cell ring of octahedra. Each of these geodesics runs through every second vertex of a skew hexagram2, which in the unit-radius, unit-edge-length 24-cell has six Template:Radic edges. The hexagram does not lie in a single central plane, but is composed of six linked Template:Radic chords from the six different hexagon great circles in the 6-cell ring. The isocline geodesic fiber is the path of an isoclinic rotation,Template:Efn a helical rather than simply circular path around the 24-cell which links vertices two edge lengths apart and consequently must wrap twice around the 24-cell before completing its six-vertex loop.Template:Efn Rather than a flat hexagon, it forms a skew hexagram out of two three-sided 360 degree half-loops: open triangles joined end-to-end to each other in a six-sided Möbius loop.Template:Efn

Each 6-cell ring contains six such hexagram isoclines, three black and three white, that connect even and odd vertices respectively.Template:Efn Each of the three black-white pairs of isoclines belongs to one of the three fibrations in which the 6-cell ring occurs. Each fibration's right (or left) rotation traverses two black isoclines and two white isoclines in parallel, rotating all 24 vertices.Template:Efn

Beginning at any vertex at one end of the column of six octahedra, we can follow an isoclinic path of Template:Radic chords of an isocline from octahedron to octahedron. In the 24-cell the Template:Radic edges are great hexagon edges (and octahedron edges); in the column of six octahedra we see six great hexagons running along the octahedra's edges. The Template:Radic chords are great hexagon diagonals, joining great hexagon vertices two Template:Radic edges apart. We find them in the ring of six octahedra running from a vertex in one octahedron to a vertex in the next octahedron, passing through the face shared by the two octahedra (but not touching any of the face's 3 vertices). Each Template:Radic chord is a chord of just one great hexagon (an edge of a great triangle inscribed in that great hexagon), but successive Template:Radic chords belong to different great hexagons.Template:Efn At each vertex the isoclinic path of Template:Radic chords bends 60 degrees in two central planesTemplate:Efn at once: 60 degrees around the great hexagon that the chord before the vertex belongs to, and 60 degrees into the plane of a different great hexagon entirely, that the chord after the vertex belongs to.Template:Efn Thus the path follows one great hexagon from each octahedron to the next, but switches to another of the six great hexagons in the next link of the hexagram2 path. Followed along the column of six octahedra (and "around the end" where the column is bent into a ring) the path may at first appear to be zig-zagging between three adjacent parallel hexagonal central planes (like a Petrie polygon), but it is not: any isoclinic path we can pick out always zig-zags between two sets of three adjacent parallel hexagonal central planes, intersecting only every even (or odd) vertex and never changing its inherent even/odd parity, as it visits all six of the great hexagons in the 6-cell ring in rotation.Template:Efn When it has traversed one chord from each of the six great hexagons, after 720 degrees of isoclinic rotation (either left or right), it closes its skew hexagram and begins to repeat itself, circling again through the black (or white) vertices and cells.

At each vertex, there are four great hexagonsTemplate:Efn and four hexagram isoclines (all black or all white) that cross at the vertex.Template:Efn Four hexagram isoclines (two black and two white) comprise a unique (left or right) fiber bundle of isoclines covering all 24 vertices in each distinct (left or right) isoclinic rotation. Each fibration has a unique left and right isoclinic rotation, and corresponding unique left and right fiber bundles of isoclines.Template:Efn There are 16 distinct hexagram isoclines in the 24-cell (8 black and 8 white).Template:Efn Each isocline is a skew Clifford polygon of no inherent chirality, but acts as a left (or right) isocline when traversed by a left (or right) rotation in different fibrations.Template:Efn

Helical octagrams and their isoclines

The 24-cell contains 18 helical octagram isoclines (9 black and 9 white). Three pairs of octagram edge-helices are found in each of the three inscribed 16-cells, described elsewhere as the helical construction of the 16-cell. In summary, each 16-cell can be decomposed (three different ways) into a left-right pair of 8-cell rings of Template:Radic-edged tetrahedral cells. Each 8-cell ring twists either left or right around an axial octagram helix of eight chords. In each 16-cell there are exactly 6 distinct helices, identical octagrams which each circle through all eight vertices. Each acts as either a left helix or a right helix or a Petrie polygon in each of the six distinct isoclinic rotations (three left and three right), and has no inherent chirality except in respect to a particular rotation. Adjacent vertices on the octagram isoclines are Template:Radic = 90° apart, so the circumference of the isocline is 4𝝅. An isoclinic rotation by 90° in great square invariant planes takes each vertex to its antipodal vertex, four vertices away in either direction along the isocline, and Template:Radic = 180° distant across the diameter of the isocline.

Each of the 3 fibrations of the 24-cell's 18 great squares corresponds to a distinct left (and right) isoclinic rotation in great square invariant planes. Each 60° step of the rotation takes 6 disjoint great squares (2 from each 16-cell) to great squares in a neighboring 16-cell, on 8-chord helical isoclines characteristic of the 16-cell.Template:Efn

In the 24-cell, these 18 helical octagram isoclines can be found within the six orthogonal 4-cell rings of octahedra. Each 4-cell ring has cells bonded vertex-to-vertex around a great square axis, and we find antipodal vertices at opposite vertices of the great square. A Template:Radic chord (the diameter of the great square and of the isocline) connects them. Boundary cells describes how the Template:Radic axes of the 24-cell's octahedral cells are the edges of the 16-cell's tetrahedral cells, each tetrahedron is inscribed in a (tesseract) cube, and each octahedron is inscribed in a pair of cubes (from different tesseracts), bridging them.Template:Efn The vertex-bonded octahedra of the 4-cell ring also lie in different tesseracts.Template:Efn The isocline's four Template:Radic diameter chords form an octagram8{4}=4{2} with Template:Radic edges that each run from the vertex of one cube and octahedron and tetrahedron, to the vertex of another cube and octahedron and tetrahedron (in a different tesseract), straight through the center of the 24-cell on one of the 12 Template:Radic axes.

The octahedra in the 4-cell rings are vertex-bonded to more than two other octahedra, because three 4-cell rings (and their three axial great squares, which belong to different 16-cells) cross at 90° at each bonding vertex. At that vertex the octagram makes two right-angled turns at once: 90° around the great square, and 90° orthogonally into a different 4-cell ring entirely. The 180° four-edge arc joining two ends of each Template:Radic diameter chord of the octagram runs through the volumes and opposite vertices of two face-bonded Template:Radic tetrahedra (in the same 16-cell), which are also the opposite vertices of two vertex-bonded octahedra in different 4-cell rings (and different tesseracts). The 720° octagram isocline runs through 8 vertices of the four-cell ring and through the volumes of 16 tetrahedra. At each vertex, there are three great squares and six octagram isoclines (three black-white pairs) that cross at the vertex.Template:Efn

This is the characteristic rotation of the 16-cell, not the 24-cell's characteristic rotation, and it does not take whole 16-cells of the 24-cell to each other the way the 24-cell's rotation in great hexagon planes does.Template:Efn

| Five ways of looking at a skew 24-gram | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edge path | Petrie polygons | In a 600-cell | Discrete fibration | Diameter chords |

| 16-cells3{3/8} | Dodecagons2{12} | 24-gram{24/5} | Squares6{4} | {24/12}={12/2} |

|

|

|

|

|

| The 24-cell's three inscribed Clifford parallel 16-cells revealed as disjoint 8-point 4-polytopes with Template:Radic edges.Template:Efn | 2 skew polygons of 12 Template:Radic edges each. The 24-cell can be decomposed into 2 disjoint zig-zag dodecagons (4 different ways).Template:Sfn | In compounds of 5 24-cells, isoclines with golden chords of length φ = Template:Radic connect all 24-cells in 24-chord circuits.Template:Sfn | Their isoclinic rotation takes 6 Clifford parallel (disjoint) great squares with Template:Radic edges to each other. | Two vertices four Template:Radic chords apart on the circular isocline are antipodal vertices joined by a Template:Radic axis. |

Characteristic orthoscheme

| Characteristics of the 24-cellTemplate:Sfn | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| edgeTemplate:Sfn | arc | dihedralTemplate:Sfn | |||

| 𝒍 | 60° | 120° | |||

| 𝟀 | 45° | 45° | |||

| 𝝉Template:Efn | 30° | 60° | |||

| 𝟁 | 30° | 60° | |||

| 45° | 90° | ||||

| 30° | 90° | ||||

| 30° | 90° | ||||

| Template:Efn | |||||

Every regular 4-polytope has its characteristic 4-orthoscheme, an irregular 5-cell.Template:Efn The characteristic 5-cell of the regular 24-cell is represented by the Coxeter-Dynkin diagram Template:Coxeter–Dynkin diagram, which can be read as a list of the dihedral angles between its mirror facets.Template:Efn It is an irregular tetrahedral pyramid based on the characteristic tetrahedron of the regular octahedron. The regular 24-cell is subdivided by its symmetry hyperplanes into 1152 instances of its characteristic 5-cell that all meet at its center.Template:Sfn

The characteristic 5-cell (4-orthoscheme) has four more edges than its base characteristic tetrahedron (3-orthoscheme), joining the four vertices of the base to its apex (the fifth vertex of the 4-orthoscheme, at the center of the regular 24-cell).Template:Efn If the regular 24-cell has radius and edge length 𝒍 = 1, its characteristic 5-cell's ten edges have lengths , , around its exterior right-triangle face (the edges opposite the characteristic angles 𝟀, 𝝉, 𝟁),Template:Efn plus , , (the other three edges of the exterior 3-orthoscheme facet the characteristic tetrahedron, which are the characteristic radii of the octahedron), plus , , , (edges which are the characteristic radii of the 24-cell). The 4-edge path along orthogonal edges of the orthoscheme is , , , , first from a 24-cell vertex to a 24-cell edge center, then turning 90° to a 24-cell face center, then turning 90° to a 24-cell octahedral cell center, then turning 90° to the 24-cell center.

Reflections

The 24-cell can be constructed by the reflections of its characteristic 5-cell in its own facets (its tetrahedral mirror walls).Template:Efn Reflections and rotations are related: a reflection in an even number of intersecting mirrors is a rotation.Template:Sfn Consequently, regular polytopes can be generated by reflections or by rotations. For example, any 720° isoclinic rotation of the 24-cell in a hexagonal invariant plane takes each of the 24 vertices to and through 5 other vertices and back to itself, on a skew hexagram2 geodesic isocline that winds twice around the 3-sphere on every second vertex of the hexagram. Any set of four orthogonal pairs of antipodal vertices (the 8 vertices of one of the three inscribed 16-cells) performing half such an orbit visits 3 * 8 = 24 distinct vertices and generates the 24-cell sequentially in 3 steps of a single 360° isoclinic rotation, just as any single characteristic 5-cell reflecting itself in its own mirror walls generates the 24 vertices simultaneously by reflection.

Tracing the orbit of one such 16-cell vertex during the 360° isoclinic rotation reveals more about the relationship between reflections and rotations as generative operations.Template:Efn The vertex follows an isocline (a doubly curved geodesic circle) rather than an ordinary great circle.Template:Efn The isocline connects vertices two edge lengths apart, but curves away from the great circle path over the two edges connecting those vertices, missing the vertex in between.Template:Efn Although the isocline does not follow any one great circle, it is contained within a ring of another kind: in the 24-cell it stays within a 6-cell ring of sphericalTemplate:Sfn octahedral cells, intersecting one vertex in each cell, and passing through the volume of two adjacent cells near the missed vertex.

Chiral symmetry operations

A symmetry operation is a rotation or reflection which leaves the object indistinguishable from itself before the transformation. The 24-cell has 1152 distinct symmetry operations (576 rotations and 576 reflections). Each rotation is equivalent to two reflections, in a distinct pair of non-parallel mirror planes.Template:Efn

Pictured are sets of disjoint great circle polygons, each in a distinct central plane of the 24-cell. For example, {24/4}=4{6} is an orthogonal projection of the 24-cell picturing 4 of its [16] great hexagon planes.Template:Efn The 4 planes lie Clifford parallel to the projection plane and to each other, and their great polygons collectively constitute a discrete Hopf fibration of 4 non-intersecting great circles which visit all 24 vertices just once.

Each row of the table describes a class of distinct rotations. Each rotation class takes the left planes pictured to the corresponding right planes pictured.Template:Efn The vertices of the moving planes move in parallel along the polygonal isocline paths pictured. For example, the rotation class consists of [32] distinct rotational displacements by an arc-distance of Template:Sfrac = 120° between 16 great hexagon planes represented by quaternion group and a corresponding set of 16 great hexagon planes represented by quaternion group .Template:Efn One of the [32] distinct rotations of this class moves the representative vertex coordinate to the vertex coordinate .Template:Efn

In a rotation class each quaternion group may be representative not only of its own fibration of Clifford parallel planesTemplate:Efn but also of the other congruent fibrations.Template:Efn For example, rotation class takes the 4 hexagon planes of to the 4 hexagon planes of which are 120° away, in an isoclinic rotation. But in a rigid rotation of this kind,Template:Efn all [16] hexagon planes move in congruent rotational displacements, so this rotation class also includes , and . The name is the conventional representation for all [16] congruent plane displacements.

These rotation classes are all subclasses of which has [32] distinct rotational displacements rather than [16] because there are two chiral ways to perform any class of rotations, designated its left rotations and its right rotations. The [16] left displacements of this class are not congruent with the [16] right displacements, but enantiomorphous like a pair of shoes.Template:Efn Each left (or right) isoclinic rotation takes [16] left planes to [16] right planes, but the left and right planes correspond differently in the left and right rotations. The left and right rotational displacements of the same left plane take it to different right planes.

Each rotation class (table row) describes a distinct left (and right) isoclinic rotation. The left (or right) rotations carry the left planes to the right planes simultaneously,Template:Efn through a characteristic rotation angle.Template:Efn For example, the rotation moves all [16] hexagonal planes at once by Template:Sfrac = 120° each. Repeated 6 times, this left (or right) isoclinic rotation moves each plane 720° and back to itself in the same orientation, passing through all 4 planes of the left set and all 4 planes of the right set once each.Template:Efn The picture in the isocline column represents this union of the left and right plane sets. In the example it can be seen as a set of 4 Clifford parallel skew hexagrams, each having one edge in each great hexagon plane, and skewing to the left (or right) at each vertex throughout the left (or right) isoclinic rotation.Template:Efn

Conclusions

Very few if any of the observations made in this paper are original, as I hope the citations demonstrate, but some new terminology has been introduced in making them. The term radially equilateral describes a uniform polytope with its edge length equal to its long radius, because such polytopes can be constructed, with their long radii, from equilateral triangles which meet at the center, each contributing two radii and an edge. The use of the noun isocline, for the circular geodesic path traced by a vertex of a 4-polytope undergoing isoclinic rotation, may also be new in this context. The chord-path of an isocline may be called the 4-polytope's Clifford polygon, as it is the skew polygonal shape of the rotational circles traversed by the 4-polytope's vertices in its characteristic Clifford displacement.Template:Sfn

Acknowledgements

This paper is an extract of a 24-cell article collaboratively developed by Wikipedia editors. This version contains only those sections of the Wikipedia article which I authored, or which I completely rewrote. I have removed those sections principally authored by other Wikipedia editors, and illustrations and tables which I did not create myself, except for two essential rotating animations created by Wikipedia illustrator JasonHise and one by Greg Egan which I have retained with attribution.Template:Efn Consequently, this version is not a complete treatment of the subject; it is missing some essential topics, and it is inadequately illustrated. As a subset of the collaboratively developed 24-cell article from which it was extracted, it is intended to gather in one place just what I have personally authored. Even so, it contains small fragments of which I am not the original author, and many editorial improvements by other Wikipedia editors. The original provenance of any sentence in this document may be ascertained precisely by consulting the complete revision history of the Wikipedia:24-cell article, in which I am identified as Wikipedia editor Dc.samizdat.

Since I came to my own understanding of the 24-cell slowly, in the course of making additions to the Wikipedia:24-cell article, I am greatly indebted to the Wikipedia editors whose work on it preceded mine. Chief among these is Wikipedia editor Tomruen (Tom Ruen), the original author and principal illustrator of a great many of the Wikipedia articles on polytopes. The 24-cell article that I began with was already more accessible, to me, than even Coxeter's Regular Polytopes, or any other book treating the subject. I was inspired by the existence of Wikipedia articles on the 4-polytopes to study them more closely, and then became convinced by my own experience exploring this hypertext that the 4-polytopes could be understood much more readily, and could be documented most engagingly and comprehensively, if everything that researchers have discovered about them were incorporated into this single encyclopedic hypertext. Well-illustrated hypertext is naturally the most appropriate medium in which to describe a hyperspace, such as Euclidean 4-space. Another essential contributor to my dawning comprehension of 4-dimensional geometry was Wikipedia editor Cloudswrest (A.P. Goucher), who authored the section of the Wikipedia:24-cell article entitled Cell rings describing the torus decomposition of the 24-cell into cell rings forming discrete Hopf fibrations, also studied by Banchoff.Template:Sfn Finally, J.E. Mebius's definitive Wikipedia article on SO(4), the group of Rotations in 4-dimensional Euclidean space, informs this entire paper, which is essentially an explanation of the 24-cell's geometry as a function of its isoclinic rotations.

Future work

The encyclopedia Wikipedia is not the only appropriate hypertext medium in which to explore and document the fourth dimension. Wikipedia rightly publishes only knowledge that can be sourced to previously published authorities. An encyclopedia cannot function as a research journal, in which is documented the broad, evolving edge of a field of knowledge, well before the observations made there have settled into a consensus of accepted facts. Moreover, an encyclopedia article must not become a textbook, or attempt to be the definitive whole story on a topic, or have too many footnotes! At some point in my enlargement of the Wikipedia:24-cell article, it began to transgress upon these limits, and other Wikipedia editors began to prune it back, appropriately for an encyclopedia article. I therefore sought out a home for expanded, more-than-encyclopedic versions of it and the other 4-polytope articles, where they could be enlarged by active researchers, beyond the scope of the Wikipedia encyclopedia articles.

Fortunately Wikiversity provides just such a medium: an alternate hypertext web compatible with Wikipedia, but without the constraint of consisting of encyclopedia articles alone. A non-profit collaborative space for students and researchers, Wikiversity hosts all kinds of hypertext learning resources, such as hypertext textbooks which enlarge upon topics covered by Wikipedia, and research journals covering various fields of study which accept papers for peer review and publication. A hypertext article hosted at Wikiversity may contain links to any Wikipedia or Wikiversity article. This paper, for example, is hosted at Wikiversity, but most of its links are to Wikipedia encyclopedia articles.

Three consistent versions of the 24-cell article now exist, including this paper. The most complete version is the expanded 24-cell article hosted at Wikiversity, which includes everything in the other two versions except these acknowledgments, plus additional learning resources. The original encyclopedia version, the Wikipedia:24-cell article, should rightly be an abridged version of the expanded Wikiversity 24-cell article, from which extra content inappropriate for an encyclopedia article has been excluded.

Notes

Template:Regular convex 4-polytopes Notelist

Citations

References

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- (Paper 3) H.S.M. Coxeter, Two aspects of the regular 24-cell in four dimensions

- (Paper 22) H.S.M. Coxeter, Regular and Semi Regular Polytopes I, [Math. Zeit. 46 (1940) 380–407, MR 2,10]

- (Paper 23) H.S.M. Coxeter, Regular and Semi-Regular Polytopes II, [Math. Zeit. 188 (1985) 559-591]

- (Paper 24) H.S.M. Coxeter, Regular and Semi-Regular Polytopes III, [Math. Zeit. 200 (1988) 3-45]

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite journal

- Template:Citation

- Template:Cite journal

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite arXiv

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Cite thesis

- Template:Cite arXiv

- Template:Cite journal

- Template:Cite journal

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite journal

- Template:Cite thesis

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite journal

- Template:Cite journal

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Cite web