History of Topics in Special Relativity/Lorentz transformation (hyperbolic)

{{../Lorentz transformation (header)}}

Lorentz transformation via hyperbolic functions

Translation in the hyperbolic plane

The case of a Lorentz transformation without spatial rotation is called a w:Lorentz boost. The simplest case can be given, for instance, by setting n=1 in the [[../Lorentz transformation (general)#math_1a|E:most general Lorentz transformation (1a)]]:

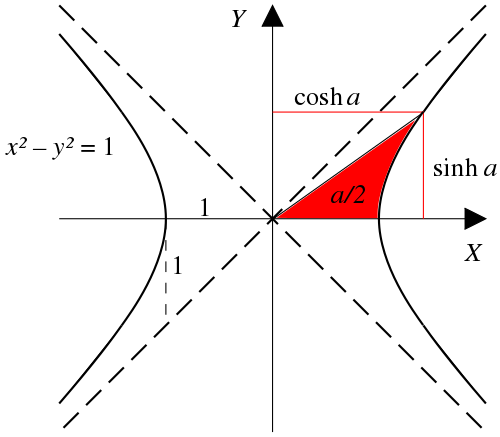

which resembles precisely the relations of w:hyperbolic functions in terms of w:hyperbolic angle . Thus a Lorentz boost or w:hyperbolic rotation (being the same as a rotation around an imaginary angle in [[../Lorentz transformation (imaginary)#math_2b|E:(2b)]] or a translation in the hyperbolic plane in terms of the hyperboloid model) is given by

Hyperbolic identities (a,b) on the right of (Template:EquationNote) were given by Riccati (1757), all identities (a,b,c,d,e,f) by Lambert (1768–1770). Lorentz transformations (Template:EquationNote-A) were given by Laisant (1874), Cox (1882), Goursat (1888), Lindemann (1890/91), Gérard (1892), Killing (1893, 1897/98), Whitehead (1897/98), Woods (1903/05), Elliott (1903) and Liebmann (1904/05) in terms of Weierstrass coordinates of the w:hyperboloid model, while transformations similar to (Template:EquationNote-C) have been used by Lipschitz (1885/86). In special relativity, hyperbolic functions were used by Frank (1909) and Varićak (1910).

Using the idendity , Lorentz boost (Template:EquationNote) assumes a simple form by using w:squeeze mappings in analogy to Euler's formula in [[../Lorentz transformation (imaginary)#math_2c|E:(2c)]]:[1]

Lorentz transformations (Template:EquationNote) for arbitrary k were given by many authors (see [[../Lorentz transformation (squeeze)|E:Lorentz transformations via squeeze mappings]]), while a form similar to was given by Lipschitz (1885/86), and the exponential form was implicitly used by Mercator (1668) and explicitly by Lindemann (1890/91), Elliott (1903), Herglotz (1909).

Rapidity can be composed of arbitrary many rapidities as per the w:angle sum laws of hyperbolic sines and cosines, so that one hyperbolic rotation can represent the sum of many other hyperbolic rotations, analogous to the relation between w:angle sum laws of circular trigonometry and spatial rotations. Alternatively, the hyperbolic angle sum laws themselves can be interpreted as Lorentz boosts, as demonstrated by using the parameterization of the w:unit hyperbola:

Hyperbolic angle sum laws were given by Riccati (1757) and Lambert (1768–1770) and many others, while matrix representations were given by Glaisher (1878) and Günther (1880/81).

Hyperbolic law of cosines

By adding coordinates and in Lorentz transformation (Template:EquationNote) and interpreting as w:homogeneous coordinates, the Lorentz transformation can be rewritten in line with equation [[../Lorentz transformation (general)#math_1b|E:(1b)]] by using coordinates defined by inside the w:unit sphere as follows:

Transformations (A) were given by Escherich (1874), Goursat (1888), Killing (1898), and transformations (C) by Beltrami (1868), Schur (1885/86, 1900/02) in terms of Beltrami coordinates[2] of hyperbolic geometry. This transformation becomes equivalent to the w:hyperbolic law of cosines by restriction to coordinates of the -plane and -plane and defining their scalar products in terms of trigonometric and hyperbolic identities:[3][R 1][4]

The hyperbolic law of cosines (A) was given by Taurinus (1826) and Lobachevsky (1829/30) and others, while variant (B) was given by Schur (1900/02). By further setting or it follows:

Formulas (3g-B) are the equations of an w:ellipse of eccentricity v, w:eccentric anomaly α' and w:true anomaly α, first geometrically formulated by Kepler (1609) and explicitly written down by Euler (1735, 1748), Lagrange (1770) and many others in relation to planetary motions. They were also used by [[../Lorentz transformation (conformal)#Darboux|E:Darboux (1873)]] as a sphere transformation. In special relativity these formulas describe the aberration of light, see [[../Lorentz transformation (velocity)#Velocity addition and aberration|E:velocity addition and aberration]].

Historical notation

Template:Anchor Mercator (1668) – hyperbolic relations

While deriving the w:Mercator series, w:Nicholas Mercator (1668) demonstrated the following relations on a rectangular hyperbola:[M 1]

Template:Anchor Euler (1735) – True and eccentric anomaly

Template:See also Template:See also

w:Johannes Kepler (1609) geometrically formulated w:Kepler's equation and the relations between the w:mean anomaly, w:true anomaly, and w:eccentric anomaly.[M 2][5] The relation between the true anomaly z and the eccentric anomaly P was algebraically expressed by w:Leonhard Euler (1735/40) as follows:[M 3]

and in 1748:[M 4]

while w:Joseph-Louis Lagrange (1770/71) expressed them as follows[M 5]

Template:Anchor Riccati (1757) – hyperbolic addition

w:Vincenzo Riccati (1757) introduced hyperbolic functions cosh and sinh, which he denoted as Ch. and Sh. related by with r being set to unity in modern publications, and formulated the addition laws of hyperbolic sine and cosine:[M 6][M 7]

He furthermore showed that and follow by setting and in the above formulas.

Template:Anchor Lambert (1768–1770) – hyperbolic addition

While Riccati (1757) discussed the hyperbolic sine and cosine, w:Johann Heinrich Lambert (read 1767, published 1768) introduced the expression tang φ or abbreviated tφ as the w:tangens hyperbolicus of a variable u, or in modern notation tφ=tanh(u):[M 8][6]

In (1770) he rewrote the addition law for the hyperbolic tangens (f) or (g) as:[M 9]

Lambert also formulated the addition laws for the hyperbolic cosine and sine (Lambert's "cos" and "sin" actually mean "cosh" and "sinh"):

Template:Anchor Taurinus (1826) – Hyperbolic law of cosines

After the addition theorem for the tangens hyperbolicus was given by Lambert (1768), w:hyperbolic geometry was used by w:Franz Taurinus (1826), and later by w:Nikolai Lobachevsky (1829/30) and others, to formulate the w:hyperbolic law of cosines:[M 10][7][8]

Template:Anchor Beltrami (1868) – Beltrami coordinates

w:Eugenio Beltrami (1868a) introduced coordinates of the w:Beltrami–Klein model of hyperbolic geometry, and formulated the corresponding transformations in terms of homographies:[M 11]

(where the disk radius a and the w:radius of curvature R are real in spherical geometry, in hyperbolic geometry they are imaginary), and for arbitrary dimensions in (1868b)[M 12]

Template:Anchor Laisant (1874) – Equipollences

In his French translation of w:Giusto Bellavitis' principal work on w:equipollences, w:Charles-Ange Laisant (1874) added a chapter related to hyperbolas. The equipollence OM and its tangent MT of a hyperbola is defined by Laisant as[M 13]

- (1)

Here, OA and OB are conjugate semi-diameters of a hyperbola with OB being imaginary, both of which he related to two other conjugated semi-diameters OC and OD by the following transformation:

producing the invariant relation

- .

Substituting into (1), he showed that OM retains its form

He also defined velocity and acceleration by differentiation of (1).

Template:Anchor Escherich (1874) – Beltrami coordinates

w:Gustav von Escherich (1874) discussed the plane of constant negative curvature[9] based on the w:Beltrami–Klein model of hyperbolic geometry by Beltrami (1868). Similar to w:Christoph Gudermann (1830)[M 14] who introduced axial coordinates x=tan(a) and y=tan(b) in sphere geometry in order to perform coordinate transformations in the case of rotation and translation, Escherich used hyperbolic functions x=tanh(a/k) and y=tanh(b/k)[M 15] in order to give the corresponding coordinate transformations for the hyperbolic plane, which for the case of translation have the form:[M 16]

- and

Template:Anchor Glaisher (1878) – hyperbolic addition

It was shown by w:James Whitbread Lee Glaisher (1878) that the hyperbolic addition laws can be expressed by matrix multiplication:[M 17]

Template:Anchor Günther (1880/81) – hyperbolic addition

Following Glaisher (1878), w:Siegmund Günther (1880/81) expressed the hyperbolic addition laws by matrix multiplication:[M 18]

Template:Anchor Cox (1881/82) – Weierstrass coordinates

Template:See also Template:See also Template:See also

w:Homersham Cox (1881/82) defined the case of translation in the hyperbolic plane with the y-axis remaining unchanged:[M 19]

Template:Anchor Lipschitz (1885/86) – Quadratic forms

Template:See also Template:See also

w:Rudolf Lipschitz (1885/86) discussed transformations leaving invariant the sum of squares

which he rewrote as

- .

This led to the problem of finding transformations leaving invariant the pairs (where a=1...n) for which he gave the following solution:[M 20]

Template:Anchor Schur (1885/86, 1900/02) – Beltrami coordinates

w:Friedrich Schur (1885/86) discussed spaces of constant Riemann curvature, and by following Beltrami (1868) he used the transformation[M 21]

In (1900/02) he derived basic formulas of non-Eucliden geometry, including the case of translation for which he obtained the transformation similar to his previous one:[M 22]

where can have values >0, <0 or ∞.

He also defined the triangle[M 23]

Template:Anchor Goursat (1887/88) – Minimal surfaces

w:Édouard Goursat defined real coordinates of minimal surface and imaginary coordinates of the adjoint minimal surface , so that another real minimal surface follows by the (conformal) transformation:[M 24]

and expressed these equations in terms of hyperbolic functions by setting :[M 25]

He went on to define as the direction cosines normal to surface and as the ones normal to surface , connected by the transformation:[M 26]

Template:Anchor Lindemann (1890–91) – Weierstrass coordinates and Cayley absolute

w:Ferdinand von Lindemann discussed hyperbolic geometry in terms of the w:Cayley–Klein metric in his (1890/91) edition of the lectures on geometry of w:Alfred Clebsch. Citing [[../Lorentz transformation (general)#Killing|E:Killing (1885)]] and [[../Lorentz transformation (general)#Poincare|Poincaré (1887)]] in relation to the hyperboloid model in terms of Weierstrass coordinates for the hyperbolic plane and space, he set[M 27]

and used the following transformation[M 28]

into which he put[M 29]

From that, he obtained the following Cayley absolute and the corresponding most general motion in hyperbolic space comprising ordinary rotations (a=0) or translations (α=0):[M 29]

Template:Anchor Gérard (1892) – Weierstrass coordinates

w:Louis Gérard (1892) – in a thesis examined by Poincaré – discussed Weierstrass coordinates (without using that name) in the plane and gave the case of translation as follows:[M 30]

Template:Anchor Killing (1893,97) – Weierstrass coordinates

w:Wilhelm Killing (1878–1880) gave case of translation in the form[M 31]

In 1898, Killing wrote that relation in a form similar to Escherich (1874), and derived the corresponding Lorentz transformation for the two cases were v is unchanged or u is unchanged:[M 32]

Template:Anchor Whitehead (1897/98) – Universal algebra

w:Alfred North Whitehead (1898) discussed the kinematics of hyperbolic space as part of his study of w:universal algebra, and obtained the following transformation:[M 33]

Template:Anchor Elliott (1903) – Invariant theory

w:Edwin Bailey Elliott (1903) discussed a special cyclical subgroup of ternary linear transformations for which the (unit) determinant of transformation is resoluble into three ordinary algebraical factors, which he pointed out is in direct analogy to a subgroup formed by the following transformations:[M 34]

Template:Anchor Woods (1903) – Weierstrass coordinates

Template:See also Template:See also

w:Frederick S. Woods (1903, published 1905) gave the case of translation in hyperbolic space:[M 35]

and the loxodromic substitution for hyperbolic space:[M 36]

Template:Anchor Liebmann (1904–05) – Weierstrass coordinates

w:Heinrich Liebmann (1904/05) – citing Killing (1885), Gérard (1892), Hausdorff (1899) – gave the case of translation in the hyperbolic plane:[M 37]

Template:Anchor Frank (1909) – Special relativity

In special relativity, hyperbolic functions were used by w:Philipp Frank (1909), who derived the Lorentz transformation using ψ as rapidity:[R 2]

Template:Anchor Herglotz (1909/10) – Special relativity

Template:See also Template:See also

In special relativity, w:Gustav Herglotz (1909/10) classified the one-parameter Lorentz transformations as loxodromic, hyperbolic, parabolic and elliptic, with the hyperbolic case being:[R 3]

Template:Anchor Varićak (1910) – Special relativity

In special relativity, hyperbolic functions were used by w:Vladimir Varićak in several papers starting from 1910, who represented the equations of special relativity on the basis of w:hyperbolic geometry in terms of Weierstrass coordinates. For instance, by setting l=ct and v/c=tanh(u) with u as rapidity he wrote the Lorentz transformation in agreement with (Template:EquationNote):[R 4]

He showed the relation of rapidity to the w:Gudermannian function and the w:angle of parallelism:[R 4]

He also related the velocity addition to the w:hyperbolic law of cosines:[R 5]

References

Historical mathematical sources

- {{#section:History of Topics in Special Relativity/mathsource|bel68sag}}

- {{#section:History of Topics in Special Relativity/mathsource|bel68fond}}

- {{#section:History of Topics in Special Relativity/mathsource|cox81hom}}

- {{#section:History of Topics in Special Relativity/mathsource|cox82hom}}

- {{#section:History of Topics in Special Relativity/mathsource|eli03}}

- {{#section:History of Topics in Special Relativity/mathsource|esch74}}

- {{#section:History of Topics in Special Relativity/mathsource|eul35}}

- {{#section:History of Topics in Special Relativity/mathsource|eul48a}}

- {{#section:History of Topics in Special Relativity/mathsource|ger92}}

- {{#section:History of Topics in Special Relativity/mathsource|glai78}}

- {{#section:History of Topics in Special Relativity/mathsource|gour88}}

- {{#section:History of Topics in Special Relativity/mathsource|gud30}}

- {{#section:History of Topics in Special Relativity/mathsource|guen80}}

- {{#section:History of Topics in Special Relativity/mathsource|kep09}}

- {{#section:History of Topics in Special Relativity/mathsource|kil93}}

- {{#section:History of Topics in Special Relativity/mathsource|kil97}}

- {{#section:History of Topics in Special Relativity/mathsource|lag70}}

- {{#section:History of Topics in Special Relativity/mathsource|lais74b}}

- {{#section:History of Topics in Special Relativity/mathsource|lam67}}

- {{#section:History of Topics in Special Relativity/mathsource|lam70}}

- {{#section:History of Topics in Special Relativity/mathsource|lieb04}}

- {{#section:History of Topics in Special Relativity/mathsource|lind90}}

- {{#section:History of Topics in Special Relativity/mathsource|lip86}}

- {{#section:History of Topics in Special Relativity/mathsource|merc}}

- {{#section:History of Topics in Special Relativity/mathsource|ric57}}

- {{#section:History of Topics in Special Relativity/mathsource|schu85}}

- {{#section:History of Topics in Special Relativity/mathsource|schu00}}

- {{#section:History of Topics in Special Relativity/mathsource|schu09}}

- {{#section:History of Topics in Special Relativity/mathsource|tau26}}

- {{#section:History of Topics in Special Relativity/mathsource|whit98}}

- {{#section:History of Topics in Special Relativity/mathsource|woo01}}

- {{#section:History of Topics in Special Relativity/mathsource|woo03}}

Historical relativity sources

- {{#section:History of Topics in Special Relativity/relsource|frank09a}}

- {{#section:History of Topics in Special Relativity/relsource|herg10}}

- {{#section:History of Topics in Special Relativity/relsource|var10}}

- {{#section:History of Topics in Special Relativity/relsource|var12}}

Secondary sources

Template:Reflist {{#section:History of Topics in Special Relativity/secsource|L3}}

Cite error: <ref> tags exist for a group named "R", but no corresponding <references group="R"/> tag was found

Cite error: <ref> tags exist for a group named "M", but no corresponding <references group="M"/> tag was found