Template:Physeq1

Please do not use this template. Instead go to Physics equations/Equations or a subpage and transclude from there.

SampleName

- Foo

<section end=SampleName/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=SampleName}}

---1 Introduction

---2 One dimensional kinematics

DefineDeltaVelocityAcceleration

- is the difference between two values of x (sometimes written as or )

Velocity is the rate at which position changes. Acceleration is the rate at which velocity changes. If the time interval is not infinitesimally small, we refer to these as "average" rates. The average velocity or acceleration is often denoted by a bar above:

- , .

Alternatives to to are the brakcet and the subscript . Instantaneous velocity and acceleration are derivatives, , , and occur in the limit that and are small. <section end=DefineDeltaVelocityAcceleration/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=DefineDeltaVelocityAcceleration}}

1DimUniformAccel

- (Note that only if the acceleration is uniform)

<section end=1DimUniformAccel/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=1DimUniformAccel}}

1dMotionCALCULUS

The distinction between average and instantaneous velocity lies in whether the time interval, approaches zero:

- ;

In the model of uniform acceleration, we take velocity to be a function of time, , and take the derivative:

- ,

where are three constants:

- is the initial position(at time, ).

- is the initial velocity (at time, ).

- is the acceleration, which remains uniform throughout all time (in this model).

<section end=1dMotionCALCULUS/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=1dMotionCALCULUS}}

---3 Two-Dimensional Kinematics

2DimKinematic

Two dimensional motion is where an object undergoes motion along the and axes "at the same time." The position of an object in two-dimensional space is defined by its coordinate.[1] By analogy with one-dimensional motion:

- .

- . It is not uncommon to replace Template:Nowrap begin Template:Nowrap end by t (i.e. to set the initial time, t0 equal to zero.) In free fall it is customary to orient the coordinate system so that gravity points in the negative y-direction, so that

- ax=0 and ay= -g , where g ≈ 9.8 m/s2 (at Earth's surface.)

<section end=2DimKinematic/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=2DimKinematic}}

DirectionOfMotion

The direction of motion is measured with respect to the x axis. At time equals t and 0, we have, respectively:

<section end=DirectionOfMotion/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=DirectionOfMotion}}

1dRelativeMotion

- is the velocity of the Man relative to Earth, is the velocity of the Man relative to the Train, and is the velocity of the Train relative to Earth. If the speeds are relativistic, define u=v/c where c = 2.998x108m/s is the speed of light, and

<section end=1dRelativeMotion/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=1dRelativeMotion}}

---4 Dynamics: Force and Newton's Laws

NewtonsThreeLaws

<section end=NewtonsThreeLaws/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=NewtonsThreeLaws}}

WeightSimple

- is the force of gravity on an object of mass, m. It is called weight, and at Earth/s surface , g ≈ 9.8 m/s2.

<section end=WeightSimple/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=WeightSimple}}

NormalFrictionRamp

- The normal to a surface is the direction perpendicular to that surface.

- is the normal force, which is the component of the contact force that is perpendicular to the surface.

- is force of friction, which is the component of the contact force parallel to the surface.

If θ is the angle of an inclined plane's inclination with respect to the horizontal, then (depending on how the rotated coordinate system is defined):

- is the component of weight in the normal direction.

- is the component of weight perpendicular to the normal direction.

<section end=NormalFrictionRamp/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=NormalFrictionRamp}}

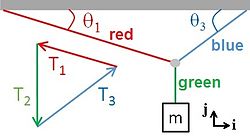

ThreeTensions

- The x and y components of the three forces on the small grey circle at the center are:

- ,

- ,

- ,

<section end=ThreeTensions/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=ThreeTensions}}

---5 Friction, Drag, and Elasticity

FrictionKineticStatic

- is the force friction when an object is sliding on a surface, where ("mew-sub-k") is the kinetic coefficient of friction, and N is the normal force.

- establishes the maximum possible friction (called static friction) that can occur before the object begins to slide. Usually .

Also, air drag often depends on speed, an effect this model fails to capture. <section end=FrictionKineticStatic/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=FrictionKineticStatic}}These equations for static and kinetic friction almost always are valid only as approximations.

---6 Uniform Circular Motion and Gravitation

UniformCircularMotion

- is the acceleration of uniform circular motion, where v is speed, r is radius, and ω is the angular frequency.

- , where T is period.

<section end=UniformCircularMotion/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=UniformCircularMotion}}

UniformCircularMotionDerive

Using the figure we define the distance traveled by a particle during a brief time interval, , and the (vector) change in velocity:

1 , and

2 (rate times time equals distance).

3 (definition of acceleration).

4 (taking the absolute value of both sides).

5 (by similar triangles). Substituting (2) and (4) yields:

6 , which leads to , and therefore:

7

<section end=UniformCircularMotionDerive/>

Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=UniformCircularMotionDerive}}

FundamentalConstantsGravity

- ≈ 6.674×10-11 m3·kg−1·s−2 is Newton's universal constant of gravity.

- ≈ 9.8 m·s-2 where M⊕ and R⊕ are Earth's mass and radius, respectively. (g is called the acceleration of gravity).

<section end=FundamentalConstantsGravity/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=FundamentalConstantsGravity}} taken from Physical constants

NewtonUniversalLawScalar

- is the force of gravity between two objects, where the universal constant of gravity is Template:Nowrap beginG ≈ 6.674 × 10-11 m3·kg−1·s−2Template:Nowrap end. If, Template:Nowrap beginM =Template:Nowrap endTemplate:Nowrap beginM⊕ ≈ 5.97 × 1024 kgTemplate:Nowrap end, and Template:Nowrap beginR =Template:Nowrap endTemplate:Nowrap beginR⊕ ≈ 6.37 × 106 kgTemplate:Nowrap end, then = Template:Nowrap beging ≈ 9.8 m/s2Template:Nowrap end is the acceleration of gravity at Earth's surface.

<section end=NewtonUniversalLawScalar/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=NewtonUniversalLawScalar}}

NewtonKeplerThirdDerive

- , where m is the mass of the orbiting object, and M>>m is the mass of the central body, and r is the radius (assuming a circular orbit).

- , where m is the mass of the orbiting object, and M>>m is the mass of the central body, and r is the radius (assuming a circular orbit). After some algebra:

<section end=NewtonKeplerThirdDerive/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=NewtonKeplerThirdDerive}}

NewtonKeplerThirdGeneralized

- , is valid for objects of comparable mass, where T is the period, (m+M) is the sum of the masses, and a is the semimajor axis: Template:Nowrap begina = ½(rmin+rmax)Template:Nowrap end where rmin and rmax are the minimum and maximum separations between the moving bodies, respectively.

<section end=NewtonKeplerThirdGeneralized/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=NewtonKeplerThirdGeneralized}}

---7 Work and Energy

EnergyConservation

- is kinetic energy, where m is mass and v is speed..

- is gravitational potential energy,where y is height, and is the gravitational acceleration at Earth's surface.

- is the potential energy stored in a spring with spring constant .

- relates the final energy to the initial energy. If energy is lost to heat or other nonconservative force, then Q>0.

<section end=EnergyConservation/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=EnergyConservation}}

WorkBasic

- (measured in Joules) is the work done by a force as it moves an object a distance . The angle between the force and the displacement is θ.

- describes the work if the force is not uniform. The steps, , taken by the particle are assumed small enough that the force is approximately uniform over the small step. If force and displacement are parallel, then the work becomes the area under a curve of F(x) versus x.

- is the power (measured in Watts) is the rate at which work is done. (v is velocity.)

<section end=WorkBasic/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=WorkBasic}}

---8 Linear Momentum and Collisions

MomentumConservation

- is momentum, where m is mass and is velocity. Momentum is conserved if the net external force is zero. The net momemtum is conserved if the net external force equal zero:

- . In a simple, one dimensional case with only two particles:

- , where the prime denotes 'final'.

To avoid subscripts and superscripts, seek ways to simplify the formula. For example if the collision is perfectly inelastic (i.e. they stick), then it is more convenient to write:

- .

<section end=MomentumConservation/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=MomentumConservation}}

---9 Statics and Torque

TorqueSimple

- is the torque caused by a force, F, exerted at a distance ,r, from the axis. The angle between r and F is θ.

* where where is the component of F that is perpendicular to r.

* where

The Template:Lw for torque is the Template:Lw (N·m). It would be inadvisable to call this a Joule, even though a Joule is also a (N·m). The symbol for torque is typically τ, the Greek letter tau. When it is called moment, it is commonly denoted M.[2] The lever arm is defined as either r, or r⊥ . Labeling r as the lever arm allows moment arm to be reserved for r⊥. <section end=TorqueSimple/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=TorqueSimple}}

TorqueCrossProduct

- uses the cross product to define torque as a vector.

<section end=TorqueCrossProduct/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=TorqueCrossProduct}}

---10 Rotational Motion and Angular Momentum

| Linear motion | Angular motion |

|---|---|

Call with {{Template:Physeq1/RotationalLinearEqnsMotionTable}}

The following table refers to rotation of a rigid body about a fixed axis: is arclength, is the distance from the axis to any point, and is the tangential acceleration, which is the component of the acceleration that is parallel to the motion. In contrast, the centripetal acceleration, , is perpendicular to the motion. The component of the force parallel to the motion, or equivalently, perpendicular, to the line connecting the point of application to the axis is . The sum is over particles or points of application.

| Linear motion | Rotational motion | Defining equation |

|---|---|---|

| Displacement = | Angular displacement = | |

| Velocity = | Angular velocity = | |

| Acceleration = | Angular acceleration = | |

| Mass = | Moment of Inertia = | |

| Force = | Torque = | |

| Momentum= | Angular momentum= | |

| Kinetic energy = | Kinetic energy = |

Call with {{Template:Physeq1/RotationalLinearAnalogyTable}}

Template:Hidden Call with {{{{Physeq1/MomentOfInertia}}}}

| Description[4] | Figure | Moment(s) of inertia |

|---|---|---|

| Rod of length L and mass m (Axis of rotation at the end of the rod) |

|

|

| Solid cylinder of radius r, height h and mass m |

|

|

| Sphere (hollow) of radius r and mass m |

|

|

| Ball (solid) of radius r and mass m |

|

Call with {{{{Physeq1/MomentOfInertiaShort}}}}

Arclength

- is the arclength of a portion of a circle of radius r described the angle θ. The two forms allow θ to be measured in either degrees or radians (2π rad = 360 deg). The lengths r and s must be measured in the same units.

<section end=Arclength/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=Arclength}}

RadianDegreeRevolutionFreqOmegaPeriod

- relates the radian, degree, and revolution.

- is the number of revolutions per second, called frequency.

- is the number of seconds per revolution, called period. Obviously .

- is called angular frequency (ω is called omega). Obviously

<section end=RadianDegreeRevolutionFreqOmegaPeriod/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=RadianDegreeRevolutionFreqOmegaPeriod}}

RotationalUniformAccel

- is the angle (in radians) where s is arclength and r is radius.

- (or Δθ/Δt), called angular velocity is the rate at which θ changes.

- (or Δω/Δt), called angular acceleration is the rate at which ω changes.

The equations of uniform angular acceleration are:

- (Note that only if the angular acceleration is uniform)

<section end=RotationalUniformAccel/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=RotationalUniformAccel}}

AngularMotionEnergyMomentum

- is the kinetic of a rigidly rotating object, where

- is the moment of inertia, equal to for a hoop of radius R and mass M (assuming the axis is through the center). For a solid disk, the moment of inertia equals .

- The generalization of Template:Nowrap beginF=maTemplate:Nowrap end for rotational motion through a fixed axis is Template:Nowrap beginτ = Iα Template:Nowrap end , where τ (called tau) is torque. If the force is perpendicular to r, then Template:Nowrap beginτ = r F Template:Nowrap end

- The total angular momentum, Template:Nowrap begin Lnet = Σ IωTemplate:Nowrap end is conserved if no net external torque is acting on a system.

<section end=AngularMotionEnergyMomentum/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=AngularMotionEnergyMomentum}}

---11 Fluid Statics

PressureVersusDepth

A fluid's pressure is F/A where F is force and A is a (flat) area. The pressure at depth, below the surface is the weight (per area) of the fluid above that point. As shown in the figure, this implies:

where is the pressure at the top surface, is the depth, and is the mass density of the fluid. In many cases, only the difference between two pressures appears in the final answer to a question, and in such cases it is permissible to set the pressure at the top surface of the fluid equal to zero. In many applications, it is possible to artificially set equal to zero, for example at atmospheric pressure. The resulting pressure is called the gauge pressure, for below the surface of a body of water. <section end=PressureVersusDepth/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=PressureVersusDepth}}

Archimedes

Pascal's principle does not hold if two fluids are separated by a seal that prohibits fluid flow (as in the case of the piston of an internal combustion engine). Suppose the upper and lower fluids shown in the figure are not sealed, so that a fluid of mass density comes to equilibrium above and below an object. Let the object have a mass density of and a volume of , as shown in the figure. The net (bottom minus top) force on the object due to the fluid is called the buoyant force:

- ,

and is directed upward. The volume in this formula, AΔh, is called the volume of the displaced fluid, since placing the volume into a fluid at that location requires the removal of that amount of fluid. Archimedes principle states:

- A body wholly or partially submerged in a fluid is buoyed up by a force equal to the weight of the displaced fluid.

Note that if , the buoyant force exactly cancels the force of gravity. A fluid element within a stationary fluid will remain stationary. But if the two densities are not equal, a third force (in addition to weight and the buoyant force) is required to hold the object at that depth. If an object is floating or partially submerged, the volume of the displaced fluid equals the volume of that portion of the object which is below the waterline. <section end=Archimedes/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=Archimedes}}

---12 Fluid Dynamics

ContinuityPipe

- the volume flow for incompressible fluid flow if viscosity and turbulence are both neglected. The average velocity is and is the cross sectional area of the pipe. As shown in the figure, because is constant along the developed flow. To see this, note that the volume of pipe is along a distance . And, is the volume of fluid that passes a given point in the pipe during a time .

<section end=ContinuityPipe/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=ContinuityPipe}}

ContinuityCALCULUS

- is the generalization of the continuity equation for incompressible fluid flow in three dimensions, where is the outward unit vector and the integral is over the entire surface.

<section end=ContinuityCALCULUS/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=ContinuityCALCULUS}}

Bernoulli

- is Bernoulli's equation, where is pressure, is density, and is height. This holds for inviscid flow.

<section end=Bernoulli/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=Bernoulli}}

---13 Temperature, Kinetic Theory, and Gas Laws

TemperatureConversion

- converts from Celsius to Kelvins.

- converts from Celsius to Fahrenheit.

<section end=TemperatureConversion/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=TemperatureConversion}}

ThermodynamicConstants

- Boltzmann's constant is kB ≈ Template:Nowrap and the gas constant is R ≈ Template:ValJ K−1 mol−1.

- The atomic mass unit ≈ Template:Nowrap is the approximate mass of protons and neutrons in the atom. (The proton/electron mass ratio is approximately 1836)

<section end=ThermodynamicConstants/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=ThermodynamicConstants}}

IdealGasLaw

- is the ideal gas law, where P is pressure, V is volume, n is the number of moles and N is the number of atoms or molecules. Temperature must be measured on an absolute scale (e.g. Kelvins).

<section end=IdealGasLaw/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=IdealGasLaw}}N<sub>A</sub>k<sub>B</sub>=R where N<sub>A</sub>= {{nowrap|6.02 × 10<sup>23</sup>}} is the Avogadro number. Boltzmann's constant can also be written in eV and Kelvins: k<sub>B</sub> ≈{{nowrap|8.6 × 10<sup>-5</sup> eV/deg}}.

AverageTranslationalKineticEnergyGas

- is the average translational kinetic energy per "atom" of a 3-dimensional ideal gas.

- is the root-mean-square speed of atoms in an ideal gas.

<section end=AverageTranslationalKineticEnergyGas/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=AverageTranslationalKineticEnergyGas}}

EnergyIdealGas

- is the total energy of an ideal gas, where degrees of freedom a three-dimensional monatomic gas.

<section end=EnergyIdealGas/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=EnergyIdealGas}}

---14 Heat and Heat Transfer

SpecificLatentHeat

- is the heat required to change the temperature of a substance of mass, m. The change in temperature is ΔT. The specific heat, cS, depends on the substance (and to some extent, its temperature and other factors such as pressure). Heat is the transfer of energy, usually from a hotter object to a colder one. The units of specfic heat are energy/mass/degree, or Template:Nowrap beginJ/(kg-degree)Template:Nowrap end.

- is the heat required to change the phase of a a mass, m, of a substance (with no change in temperature). The latent heat, L, depends not only on the substance, but on the nature of the phase change for any given substance. LF is called the latent heat of fusion, and refers to the melting or freezing of the substance. LV is called the latent heat of vaporization, and refers to evaporation or condensation of a substance.

<section end=SpecificLatentHeat/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=SpecificLatentHeat}}

PowerRateHeatTransfer

The rate of heat transfer is Q/t (or dQ/dt) and has units of "power": Template:Nowrap begin1 Watt = 1 W = 1J/sTemplate:Nowrap end

- is rate of heat transfer for a material of thermal conductivity, k, of area, A, and thickness, d. (In this model, the thickness is assumed uniform over the area, and no heat flows through the sides.) The thermal conductivity is a property of the substance used to insulate, or subdue, the flow of heat.

<section end=PowerRateHeatTransfer/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=PowerRateHeatTransfer}}

StefanBoltzmannLaw

- is the power radiated by a surface of area, A, at a temperature, T, measured on an absolute scale such as Kelvins. The emissivity, e, varies from 1 for a black body to 0 for a perfectly reflecting surface. The Stefan-Boltzmann constant is .

<section end=StefanBoltzmannLaw/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=StefanBoltzmannLaw}}

---15 Thermodynamics

StateVariables

- Pressure (P), Energy (E), Volume (V), and Temperature (T) are state variables (state functionscalled state functions). The number of particles (N) can also be viewed as a state variable.

- Work (W), Heat (Q) are not state variables.

<section end=StateVariables/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=StateVariables}}

EntropyMonatomic

- , is the entropy of an ideal , monatomic gas. The constant is arbitrary only in classical (non-quantum) thermodynamics. Since it is a function of state variables, entropy is also a state function.

<section end=EntropyMonatomic/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=EntropyMonatomic}}

HeatEngine

A point on a PV diagram define's the system's pressure (P) and volume (V). Energy (E) and pressure (P) can be deduced from equations of state: Template:Nowrap beginE=E(V,P) and T=T(V,P)Template:Nowrap end. If the piston moves, or if heat is added or taken from the substance, energy (in the form of work and/or heat) is added or subtracted. If the path returns to its original point on the PV-diagram (e.g., 12341 along the rectantular path shown), and if the process is quasistatic, all state variables Template:Nowrap return to their original values, and the final system is indistinguishable from its original state.

- Net work done equals area enclosed by the loop. This are is often written as a closed line integral:

- work done on or by the engine each cycle.

- : The net heat Qin that enters at each cycle equals the work done Wout.

- Remember: Area "under" is the work to get from one point to the other; Area "inside" is the total work per cycle.

<section end=HeatEngine/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=HeatEngine}}

IsothermalWork

In an isothermal expansion (contraction), temperature, T, is constant. Hence P=nRT/V and substitution yields,

<section end=IsothermalWork/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=IsothermalWork}}

SecondLawThermo

- is the work done on a system of pressure P by a piston of voulume V. If ΔV>0 the substance is expanding as it exerts an outward force, so that ΔW<0 and the substance is doing work on the universe; ΔW>0 whenever the universe is doing work on the system.

- is the amount of heat (energy) that flows into a system. It is positive if the system is placed in a heat bath of higher temperature. If this process is reversible, then the heat bath is at an infinitesimally higher temperature and a finite ΔQ takes an infinite amount of time.

- is the change in energy (First Law of Thermodynamics).

<section end=SecondLawThermo/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=SecondLawThermo}}

---16 Oscillatory Motion and Waves

algebraSHO

- describes oscillatory motion with period T. The amplitude, or maximum displacement is . Alternative notation includes the use of instead of ). Using by allows us to write this in terms of angular frequency, ω0:

- , where we have introduced a phase shift to permit both sine and cosine waves. For example, .

- holds for a mass-spring system with mass, m, and spring constant, ks.

- holds for a low amplitude pendulum of length, L, in a gravitational field, g.

- is the potential energy of a mass spring system. This equation can also be used for a pendulum if we replace the spring constant by an effective spring constant .

<section end=algebraSHO/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=algebraSHO}}

SHO

- describes an oscillating variable. The velocity and acceleration are:

- , where . The acceleration is given by:

- , where

- . Note also that the maximum force obeys, , and that

- is the total energy (which also equals the maximum kinetic energy, as well as the maximum potential energy (with ks being the spring constant).

- x(t) obeys the linear homogeneous differential equation (ODE), , with ω being a (constant) parameter of the ODE.

<section end=SHO/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=SHO}}

FrequencyWavelengthSpeed

- relates the frequency, f, wavelength, λ,and the the phase speed, vp of the wave (also written as vw) This phase speed is the speed of individual crests, which for sound and light waves also equals the speed at which a wave packet travels.

- describes the n-th normal mode vibrating wave on a string that is fixed at both ends (i.e. has a node at both ends). The mode number, n = 1, 2, 3,..., as shown in the figure.

<section end=FrequencyWavelengthSpeed/>

Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=FrequencyWavelengthSpeed}}

---17 Physics of Hearing

SpeedSound

- is the the approximate speed near Earth's surface, where the temperature, T, is measured in Kelvins. A theoretical calculation is where for a semi-classical gas with degrees of freedom. For a diatomic gas such as Nitrogen, Template:Nowrap beginγ = 1.4.Template:Nowrap end

<section end=SpeedSound/> Call with {{Physeq1|transcludesection=SpeedSound}}

References

- No such template exists in Physeq1